Sometimes when I discuss gun shows with people, they feel like I am running them down. I am not trying to at all. I grew up going to gun shows with my father in the late 1980s and all through the 1990s. It was fun and exciting. You never knew what you were going to find. It was one big treasure hunt!

While guns have been collected for centuries mostly by the aristocracy of Europe, gun collecting in the United States is a fairly new hobby that started just after World War II. There were a few early pioneer dealers like Theodore Dexter and Bannerman’s Island, but largely, the older guns had little interest or use. Guns were viewed simply as tools. During WWII, 16 million men served in the Armed forces and, of course, were exposed to guns of all different types. Everyone who served in the European theatre wanted to take a Luger home. All sorts of militaria and European guns were brought back as souvenirs.

Radio broadcasting began in the 1920s. Between 1940 and 1950, the number of stations multiplied by 342%! Also, during this time, television came into being. From the early 1950s through the early to mid-1960s, Westerns dominated the programming on both Radio and TV, with the most popular show being Gunsmoke.

These two events gave birth to gun collecting in the United States as we know it today. Almost all the Gun collecting clubs today were formed in the 1950s through the 1970s. Especially the regional clubs such as the Houston Gun Collectors Association and the Texas Gun Collectors Association, which were both formed in 1950. People wanted to meet at these clubs and buy, sell, and trade guns, but also to learn and compare what they had with what other club members had. Eventually, these club meetings turned into gun shows, which would typically take place a couple of times a year.

Back in the early days of collecting, these were really big deals for the enthusiasts. We are so spoiled today of getting almost anything you want sent overnight if you wish, or at worst, you might have to wait a week. Back then, you only had one or two opportunities in a year to find something for your collection unless you wanted to travel.

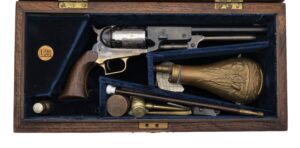

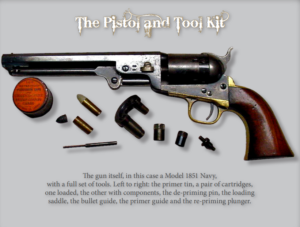

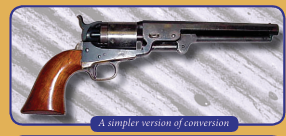

By the 1980s and through the 1990s, promoters had jumped into the mix who had nothing to do with a collecting club. I remember walking through the Houston shows as a kid and seeing everything from Colt percussion revolver to 1970s S&Ws and of course the barrels of SKS rifles that were priced $49.95 at times. It was really something special, and no one realized how good it was until 1993 with the Clinton gun legislation. Back then, anyone could get a Federal Firearms License, whether you had a storefront or not. There were a tremendous number of people who had an FFL who did not, and just set up at gun shows. Upon the passing of the Brady bill, there was a mass exodus of Federal firearms licensed dealers. Approximately 234,000 dealers maintained their license before the passing, and that number dropped to 52,000 a few years after the passing. My belief was that this was the first nail in the coffin of the gun shows.

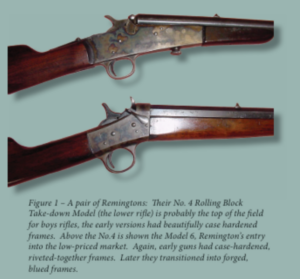

The biggest killer, though, is the internet. Simultaneously, as the gun legislation was being enacted, the internet began to take off. In 1993, there were over 6 million internet users in North America, and in 1994, the number had doubled. By the year 2000, there were 143 million internet users, and as of 2021, there are 502 million internet users in North America. During the course of time, people’s buying habits have changed significantly. Slowly but surely, the dealers realized it was much easier to list their inventories online and reach customers they would have never met at a show and the consumer grew disinterested in going to shows in general. All the collector’s guns at shows all but disappeared, and the show became filled with beef jerky, T-shirts, cheap knives, and junk guns. Today, there only exists a handful of shows that have a significant presence of collectible guns.

In 2024, there was a ruling by the ATF that redefined the definition of “engaged in Business.” If you are “engaged in business,” then you must have a Federal firearms License. While there is an injunction on this as of this writing, what it effectively does is require a dealer to go between and conduct a background check between every buyer and seller. Gone are the days of you trading guns with a fellow club member, or if you decide you want to carry your gun into a show and see who will make an offer on it. I am not necessarily saying this is a good or bad thing, but I do believe this will be detrimental to the gun shows.