Orison Blunt of Blunt & Syms

By James B. Whisker, Ph.D.

Orison Blunt was born in Gardiner, Maine, in 1816. At the age of fourteen, he went to sea as a cabin boy. He soon tired of this trade and moved to New York City, where he entered into an apprenticeship in the gunsmith’s trade. It is unknown with whom he served his apprenticeship, but he met there another apprentice, William Syms, with whom he soon formed a partnership in the gunmaking business at 44 Chatham Street.1 As business prospered, Blunt & Syms moved to 177 Broadway.

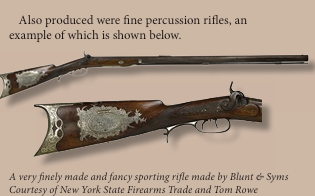

The new five-volume set, The New York State Firearms Trade, Volume 2, contains much directory information on Blunt, his partner Syms, and the firm of Blunt & Syms. The set offers essentially nothing on the lives of Blunt and Syms. There is no question but that the firm made some of the finest, most artistically meritorious guns made in the city. While we do not know which of the partners performed what specific tasks, the guns exhibit the finest workmanship: wood-to-metal fit is excellent, the engraving is of superior quality, and the overall architecture is pleasing. One example, pictured below, is of a fine set of dueling or traveling pistols that are marked “Blunt & Syms, New York”. The engraving is very fine, and the breeches are inlaid with gold and silver bands, and the overall quality is of the highest order.

Lower-end single-shot and Deringer-style pistols in several sizes and calibers were also made. These may have been the least expensive of firearms offered by Blunt & Syms, but their quality of manufacture is every bit as good as the higher-end guns. A very fine single-shot pistol with an iron forend is shown below, along with a scarce ring trigger single-shot pistol.

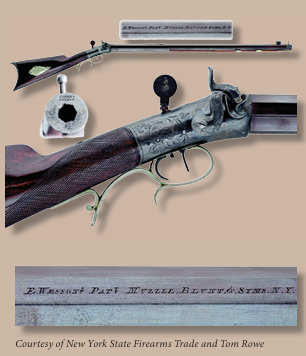

In addition to arms products of their own manufacture, they sold imported firearms, a few arms of domestic manufacture, tools, gunsmiths’ implements, and “all kinds of gun materials for Manufacturers.” In the 27 October 1849 issue of the Spirit of the Times, they represented Edwin Wesson as agents for his “patent muzzle rifles”, which they and Wesson warranted as “superior to all others.” Edwin Wesson was the elder brother of Daniel and Franklin Wesson. A slightly later advertisement, following Wesson’s untimely death, offered the arms at close-out prices. This advertisement was in the 13 April 1850 copy of the Spirit of the Times:

Wesson’s Cast Steel Rifles Blunt & Syms, 177 Broadway

Have on hand a quantity of these justly celebrated Rifles, being the entire stock of Mr. E. Wesson, including those in process of manufacture at the time of Mr. Wesson’s demise. These guns are well known for their extraordinarily good target shooting, and as no more are being made, amateurs would do well to secure them whilst the opportunity offers. They are in complete order, including slug mold, ball pounder, starter, &c., &c., and will be sold low.

A very nice target rifle is shown below. Note the barrel address has “E. Wesson’s Patented Muzzle” preceding the “Blunt & Syms” name.

The Blunt & Syms manufactory was extensive. The U.S. Census of Industry for 1850 shows a facility with capital investment of $10,000, employing 50 hands with a monthly payroll of $1,000, and powered by steam. Over the previous twelve months ,it had made guns valued at $26,250, and used raw materials that cost $13,000.

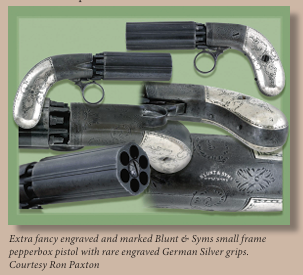

Blunt was an innovative entrepreneur. He patented a pepperbox, U.S. patent number 6966, dated 25 December 1849. These arms are well known and frequently encountered. In his book Pepperbox Firearms, Jack Dunlap devoted considerable space to the Blunt & Syms products. These are among the finest arms of their type.4 These pepperboxes were made in several styles and sizes. They differ in their operation from that of the usual American pepperbox in that the bottom barrel is fired as opposed to the usually seen top barrel being fired with a hammer that provides a rudimentary rear sight. The Blunt & Syms pepperboxes had no sights.

Captain Samuel Walker helped to design a new Colt revolver, and Samuel Colt arranged with Eli Whitney, Jr., to manufacture it at his Whitneyville, Connecticut factory. The two gunsmiths chosen to assist were Orison Blunt and Thomas Warner. The result was the Model 1847 Whitneyville-Walker, also known in a slightly trimmed form as the first Colt Dragoon.

The last year the firm of Blunt & Syms was listed in New York directories seems to have been for the years 1854-1855, which would have been subscribed and prepared in 1853. Swinney and his associates did not report locating any newspaper legal advertisement or other document showing the formal dissolution of the partnership. Neither do we have any document showing that Blunt had purchased the assets of the firm or that a third party had purchased the manufactory. This is odd since the facility was extensive.

Orison Blunt entered politics in 1853, standing for and winning the election in New York’s third ward for alderman. He continued to serve in that position through 1861, representing the 15th ward after 1857. He was firm in his resolve to battle corrupt contracts and sweetheart deals for which the Democrats of Tammany Hall were infamous. Typical of his vigilance was his outspoken opposition to the paving scandal in which a contractor was awarded an uncompetitive bid of $7.50 per square yard for paving streets, an unheard-of price at the time. Blunt introduced the Belgian [trap-block] paving system, which came in at a cost of $1.90 per square yard.

As an accomplished practical engineer, Blunt championed steam fire-engines, then in their infancy. He personally inspected various engines and made recommendations for their improvement. He chose those to be purchased in a unique way: he persuaded the Common Council to offer a prize for the best steam fire-engine and thus caused the various manufacturers to place their wares in competition with other vendors.7 He was outraged at the cost of building the courthouse and led an investigation into the contracts for construction.

In the earliest months of the American Civil War, several practical gunsmiths, including Orison Blunt, sought to capitalize on the paucity of arms. Those made by P.S. Justice of Philadelphia used recycled parts from the U.S. Model 1816 muskets, whereas others, including Blunt’s, used many imported parts. This author recalls that when he first began to study antique arms, what are now positively identified as J.P.

Moore’s Sons Enfield-style muskets were then sold as Blunt arms. Swinney and others cite the article in Gun Report by the late Robert Reilly, asking whether the Moore rifle musket was not a product of Orison Blunt.8 William B. Edwards also seems to have confused Blunt’s arms with those of J. P. Moore’s Sons.9 The address of Blunt’s new gun shop was 118 Ninth Street, New York City.

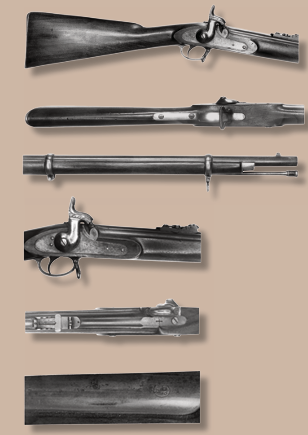

The real Blunt Enfield is illustrated here. It has a forty (40) inch-long barrel, and a marking CP/B, which should assist in separating it from the Pattern 1853 British arm. Otherwise, it appears essentially identical. British Enfields, of course, invariably have lock and barrel markings and not uncommonly small stampings all over the stocks. Blunt was initially to have supplied 20,000 stands of these rifle-muskets, but only 500 or so seem to have been manufactured. There are various explanations for the rift that quickly opened between Blunt and U.S. Ordnance. The claim that the arms were not proved seems to be obviated by the fact that the CP/B is usually interpreted as a proof mark.

A more serious consideration was that of interchangeability of parts. This had been an Ordnance desire since the days of John H. Hall at the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry. One recent study, Harpers Ferry and the New Technology, argues that the Army did not want Hall’s breech-loading rifle but rather wanted to adopt his system of the interchangeability of parts.10 When Ordnance considered contracts for the U.S. Model 1861 rifle musket, it chose only such arms firms as could meet this requirement. Other contracts were given to manufacturers that had never made arms but could manufacture products with such precision as would allow for full interchangeability. Blunt’s manufactory was not prepared to make arms with such precision, and still created most parts by hand.

Then there was a question of serviceability. There is no question that Blunt & Syms had made fine, beautiful, functional, and serviceable arms. Mass production of military arms presented problems all its own. Like Philip S., Justice Blunt seemed to have filled its initial contract with arms deemed inferior by Ordnance. Among the early Civil War arms, made with non-interchangeable parts, none seems ever to have merited federal inspection cartouches. Norm Flayderman, writing about the Justice contracts, thought that they represented “a patriot’s attempt to make quick deliveries for the Civil War effort.”11 Another point of view tends clearly toward accusations of wartime profiteering.

Finally, there was the additional diplomatic problem known as the Trent Affair. On 8 November 1861, the American Naval vessel San Jacinto stopped the British vessel Trent and removed two Confederate diplomats, James M. Mason and John Slidell, who had embarked from Havana, Cuba. Great Britain retaliated by embargoing many products, including war materials. After the Trent Affair was resolved, the new Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, required that contractors buy American, eschewing foreign raw materials and parts. The Blunt Enfield muskets were assembled in America, but nearly all parts were made in England.

On 18 March 1862, new Secretary of War Edwin Stanton appointed Robert Dale Owen, son of Utopian socialist Robert Owen, and a former Secretary of War, Judge Joseph Holt, along with Ordnance Major P. V. Hagner, to a commission to study contracts let under Stanton’s predecessor, Simon Cameron. Case number fourteen (14) involved Orison Blunt. The Holt-Owen Commission found that initially, Blunt had proposed to import 20,000 stands of British Enfield muskets. On 10 September 1861, Ordnance Chief General James Ripley informed Blunt that he would accept only American-made arms and that the arms would be inspected. Ordnance would pay $18 per stand only for such arms as would pass inspection. Blunt clearly understood that the arms would not have interchangeable parts and that he was to supply 12,000 stands between January 1862 and January 1863. The Holt-Owen Commission allowed deliveries to continue through July 1862, but the numbers were not to exceed 3000 stands. There was discussion involving the number of arms Blunt’s manufactory could produce. Blunt claimed he might deliver no less than 500 per month and perhaps as many as 1500. The accepted figure, absent any clear evidence, is that Blunt delivered about 500 stands in total. At one point, Blunt claimed to be making 300 barrels per week; this may have been somewhat optimistic.

Of the various gunmakers who offered their services at the beginning of the war, only Moore’s Sons, Justice, and Blunt seem to have made any significant numbers of arms. The fate of all the early contract arms is unclear. Some Moore rifle muskets are marked L S M, which has been interpreted as Louisiana State Militia, a Union-sponsored black paramilitary organization headquartered in occupied New Orleans. The scarcity of Blunt muskets suggests that somewhere they had been used sufficiently to render them scarce, if not downright rare.

During the U.S. Civil War, Orison Blunt also functioned as a bounty broker.13 He authored the Report of Orison Blunt to the Loyal National League14 which called for additional volunteers and for strong support for the Union government. His great concern was the drafting of poor men with large families and their use as substitutes by wealthier citizens who could avoid service by paying a bounty.

Blunt headed the Union Defense Committee, which had as its primary task the support of the state militia. To arm its soldiers, the Committee authorized Blunt on 26 May 1861 to purchase small arms and ammunition. His first purchase was of 1050 Sharps rifles. Eventually, the Committee assisted in arming the 14th Regiment from Brooklyn; the Fifth New York Volunteers, known as Zouaves; the 9th New York Volunteers, also Zouaves; the 10th and 2nd New York Volunteer Militia. They also purchased several steamers for naval use, the most famous of which was the Quaker City.

By the time of the Civil War, Democratic politics in New York City had become corrupted by Tammany Hall’s control. In 1863, Tammany named as its candidate

to become New York’s 77th mayor, one Francis I. A. Boole, a politician of such low reputation that a reform group formed within the party. Known as McKeon Democracy, it was nominated in opposition by C. Godfrey Gunther. In addition to reform politics, a second theme figured into the mayoral race: the New York draft riots of 1863. The first Republican mayor, George Updyke, failed to contain the riot and otherwise failed to distinguish himself during the riots. Few were more vocal in criticism than Blunt, who then replaced Updyke and became the Republican nominee.16 Gunther won with a 6,000 margin over Boole and 10,000 over Blunt.

Blunt died in April 1879. His obituary notes that although technically he died of dropsy (known now as congestive heart failure), physicians had also noted that a growth of a tumor in his chest had displaced his heart. It was initially diagnosed some three years earlier, and Blunt had progressively weakened.

William Syms survived his former partner by several decades. He was born in West Hoboken, New Jersey, on 25 November 1826. After the dissolution of Blunt & Syms, he moved to 112 Palisade Avenue, West Hoboken, where he remained until his death in August 1902. Apparently, he did not engage in the gunsmith’s trade after he left Orison Blunt. He became a real estate speculator. He served as town treasurer for a few years, with street paving and improvement being his great interest. He was a member of the Baptist Church and presented the congregation with a chapel at a cost of $7,000. He also paid for a public fountain in the city park.17

Patent Infringement

In October 1849, Ethan Allen of Norwich, Connecticut, filed suit against Blunt and Syms of New York, alleging infringement on his patent of 3 August 1844. The suit had begun in court in Massachusetts on 24 June 1844, and this court then found that Allen had been deprived of the profits of $11,700 by the violation of his patent. Blunt alleged that the Massachusetts court had no jurisdiction over him because of the diversity of citizenship and the fact that neither plaintiff nor defendant was a citizen of Massachusetts. Blunt also complained that the award was determined by a Master of the Court and not by a jury of his peers. The Court in New York ruled against Blunt

The Court held that “any Circuit Court of the United States, or any District Court, having the powers and jurisdiction of a Circuit Court” could hear cases involving patents. It also noted that such courts “may” increase the damages, not exceeding three times the amount of the verdict.” Nevertheless, Allen failed to prevail because of a defect in service rather than on substantive grounds. In the judgment “the plaintiff failed to recover, because it did not affirmatively appear on the face of the record from that court, that the defendant was personally served with process within the district.” This principle of law became a precedent cited in many subsequent cases.

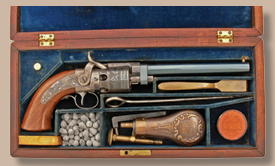

In October 1852, Colt Firearms filed suit against Massachusetts Arms and its principals, Edwin Leavitt and Hiram Terry, for violation of its patent, which, Colt alleged, included revolving arms of any sort. The case was heard in the U.S. District Court for New York, and the verdict was in Colt’s favor. Following is a nice example of a Wesson & Leavitt Belt Model manufactured by the Massachusetts Arms Company, cased with all of its accessories, that was the subject of the lawsuit.

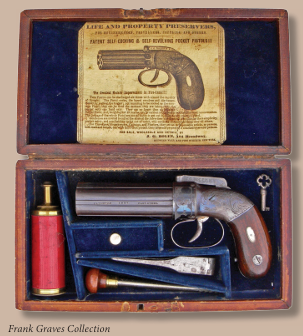

In a broadside, dated 10 November 1852, Colt advised that it would seek patent protection against all invasions. Based on the court’s decision that included all manufacturers of pepperbox firearms, including Allen & Thurber, Marston & Sprague, and, of course, Blunt & Syms. Allen & Thurber was the largest manufacturer, so it attempted to prevent troubles by reaching an agreement with Colt. It paid Colt $15,000 and promised to pursue other patent infringements according to Samuel Colt: Art, Arms and Invention by Herbert H. Houze19. Pictured below is a cased Allen & Thurber medium-sized pepperbox pistol marked J. G. Bolen of New York, who was a primary agent for Allen & Thurber guns

The two patent infringement cases may well have been the cause of the abandonment by Blunt & Syms of the manufacture of pepperboxes. They had escaped the first judgment on a technicality and faced possible action on the second by Colt or by Allen & Thurber. By the standards of our day, the position of the court in giving such an expanded interpretation of Colt’s patent is ludicrous and is, in its own way, as absurd as the Rollin White patent case.