Team Creedmoor – America’s First Sports Heroes

By Dick Salzer

Background

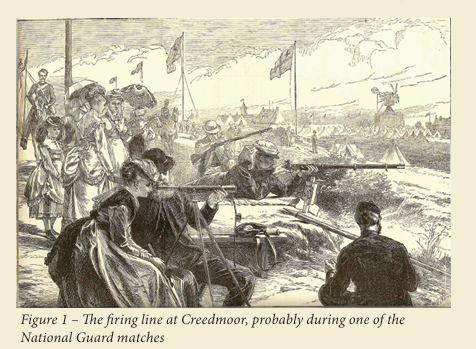

It may be hard to imagine these days of constantly televised sporting events and other forms of diversion. Still, less than 150 years ago spectators from New York City — ladies in bustles and parasols, men in spats and high hats — all dressed in their Sunday finery, boarded trains to travel a dusty 15 miles out onto Long Island just to watch shooting matches, often on steamy, humid days For a few decades, national pride hung on the exploits of teams of shooters representing United States, England, Ireland and other nations.

It all started in the United States following the Civil War. The military leadership, especially on the Union side, was bitterly disappointed in the marksmanship of both conscripts and volunteers. Two former Union officers, Col. William C. Church and Gen. George Wingate, set out to improve that situation by popularizing shooting as a sport across the country. The complete story is well told in an American Rifleman article by Roy Marcot. Their efforts resulted in the formation of an organization that we now know as the National Rifle Association

In November of 1871, the National Rifle Association was granted a charter by the State of New York. Another former Union general, Ambrose Burnside, was named as its first president. The Charter’s purpose was to “promote and encourage rifle shooting on a scientific basis”, and as will be seen in this article, no stone was left unturned to achieve that goal.

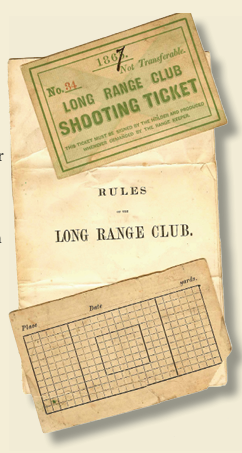

One of the organization’s first tasks was to find a place to shoot. A search for a site near New York City resulted in the purchase, with the help of the State, of a 70-acre tract of land on the north shore of Long Island. The area, known as Creed’s Farm, was located alongside the tracks of the Long Island Rail Road, making future access very convenient. As the site was developed, it was renamed “Creedmoor”, probably based on the moor-like appearance of the terrain. By 1873, the site was fully developed with firing points set at 200, 400, 500, 600, 800, 900, and 1,000 yards. The official opening date was April 25, 1873.

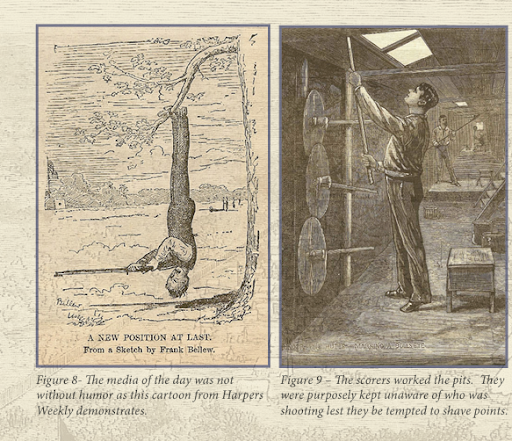

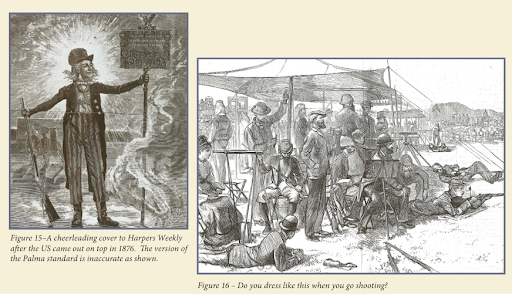

Sporting events and venues like baseball, which were shortly to become and remain popular, were in their infancy at the time. The media of the day extolled the accomplishments of prominent shooters, much as they do today’s sports heroes. The railroad erected a new station at Creedmoor, and long-range target shooting became a major spectator sport. The clothing of the day involved shirt fronts, collars, cravats, tall hats, and spats, even for laborers. Shooting attire was especially elegant, and the spectators togged out as if they were heading for the opera.

In the beginning days, competition at Creedmoor was principally between units of the National Guard and Army regulars — their first formal match was held in October of 1873.

Challenges

On the other side of the Atlantic, the English had been involved in serious competitive long-range shooting since the early 1860s. Irish and British shooters had battled one another for years at Wimbledon, with the English usually emerging victorious. In 1873, however, the Irish finally beat the British and were feeling invincible. Word had leaked out that the Americans were getting into competitive long-range shooting. Nothing could be more natural than that they issue a challenge to their American counterparts. In 1874, that challenge was sent to the American team through a letter published in the New York Herald for a match to be held on their own home turf at Creedmoor. The challenge was accepted, and the Irish boarded a ship for New York. The Irish chose to use their cherished muzzle-loading Rigby Rifles, the Americans, their breech-loading Remingtons or Sharps rifles.

In the spirit of brotherhood, the Irish captain, Arthur Leech, procured and offered a beautifully crafted tankard to be awarded to the winner of the match.

On a sweltering day in September 1874, the two teams began a day-long course of firing, which involved each of the five team members on each side firing 40 rounds each at targets 800 and 1,000 yards distant. When the smoke cleared, the Americans had upset the highly favored Irish by a slim margin — 934 to 931 (out of a possible 1,000). The resulting publicity ignited a nationalistic flame, and suddenly, long-range target shooting became a country-wide mania.

The next year, a repeat match, answering another challenge from the Irish, resulted in another American win. Most Irish teams, after the match, placed orders for the American breech loaders before returning to Ireland.

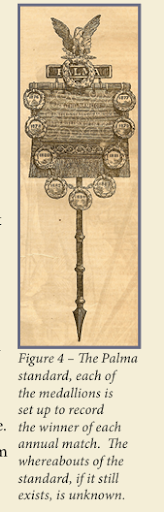

A year later, in 1876, in celebration of the Centennial of the United States, the National Rifle Association issued a challenge to riflemen of the world to come to Creedmoor to compete for the Centennial Trophy, commissioned from Tiffany. The trophy was seven and a half feet tall and patterned after a Roman standard. It bore a panel with a wreath, an eagle, and fasces. The word “PALMA” was prominently displayed, along with the phrase “In the name of Riflemen of the World” within the panel. Nine plaques were suspended from a chain stretching from corner to corner, bearing dates 1876 to 1884, intended to be engraved with the names of winners from the current and subsequent matches.

The format of the match had changed to require each shooter to fire 15 rounds at each of 800, 900, and 1,000-yard targets on each of two successive days. Teams arrived from Australia, Canada, England, Scotland, and Ireland. After fierce competition, the Americans emerged as the winners for the third time. Each member of the winning team was presented with a miniature of the Centennial trophy rendered in silver and gold. The whereabouts of the original trophy itself are not known. However, the Palma matches, as they became known, continue in modified form to this day.

Harper’s Weekly reports that in 1877, a crowd of more than 10,000 turned out to watch the Americans beat the opposition for a fourth time. By this time, the superiority of the breech-loader was clearly established, and rifle manufacturers besides Sharps and Remington were competing for the market. Subsequent matches between the Americans and British resulted in a mixture of outcomes. The matches continued throughout the 1880s, but by the 1890s, interest had waned, and the property was deeded back to the state, which subsequently constructed a facility called Creedmoor Mental Hospital that survives to this day. The NRA range was transferred to Sea Girt, New Jersey.

The Guns

The guns themselves represented the highest level of quality possible at the time. The makers all knew that their reputations were closely tied to the performance of their products.

In the beginning ,the market was pretty much controlled by Sharps and Remington. Both manufacturers produced arms that any shooter would be proud to own and prize.

- The rules for gun design were simple:

- The minimum weight, unloaded, was 10 pounds

- Sights were to be metallic, no telescopes or glass permitted

- Trigger pull must be at least 3 pounds; no set triggers permitted

- Shotgun-style butt plates. Figure 10 – Another panoramic view of the shooting grounds

- No artificial rests

These simple rules resulted in designs with long (32 to 36 inch) barrels; calibers were .44 or .45 for the 1000-yard competition, .40 caliber for mid-range shooting. The front sights were windage-adjustable and usually equipped with spirit levels. The rear sights were tall peep-sights usually set up for positioning on either the tang or extreme end of the butt stock. As the shooting sport gained in popularity, other makers joined in — Wesson, Maynard, Ballard, Providence Tool Company, and even the National Armory at Springfield all made Creedmoor-style rifles.

Curiously, Winchester chose not to compete. In fact, they actually issued a statement designed to belittle the entire activity. The following is from their 1875 catalog:

“The legitimate object of the Creedmoor Range and that for which it received its charter and liberal aid from the State of New York was to perfect the soldier in the use of his weapon, and is of great national importance; but is there not a danger of its being prostituted to a smaller use, by getting into the control of a few wealthy gun manufacturers, to be used as a machine for advertising their wares?”

Scientific Rifle Shooting

Every aspect of rifle shooting was subjected to the most extreme scrutiny. Each element was dissected, and the most introspective technology was applied:

- The barrels of breech-loaders and muzzle-loaders alike were cleaned and dried between shots. In fact, the ease with which breech-loaders could be cleaned was a significant advantage compared to swabbing a muzzle-loader

- The sights were as precise and elaborate as manufacturing technology could make them. They were a marvel of machining excellence and were built like today’s micrometers with precise Vernier adjustments and locking devices. Front sights usually contained liquid leveling devices so the rifles could be held in perfect vertical alignment.

- Bullets were made in smooth-sided molds and weighed to assure identical lead content. Paper patches were wrapped around the bullets to avoid scars from the rifling grooves after they left the muzzle, which might affect accuracy. They were often loaded using an insertion tool, separate from the cartridge casing that held a carefully weighed powder charge covered by a wax disc. The gunpowder itself was tested for strength before each contest.

- The main ingredients, the men themselves, were subjected to a training regimen that would put today’s professional athletes to shame. Restrictions on food, drink, sexual activity, mode of dress, conduct, and other everyday aspects were codified and enforced. Personality profiles were considered. Selection of men who “talked but little and were serious of purpose” was preferred.

- During practice and in matches, every shot was recorded and documented along with wind conditions, weather notations, and other data for post-match analytics.

- As shooting progressed, the time intervals between shots were spaced and timed to let barrel temperatures stabilize from shot to shot.

- In spite of Winchester’s disparaging remarks and in spite of the fact that the concept ran out of gas in the 1890s, the Creedmoor Matches occupy a special place in American arms lore. The legacy of scientific shooting had its birth during those years.

Further Reading

Gildersleeve, Judge H.A., Rifles And Marksmanship, New York, 1878

Grant, James J., More Single Shot Rifles, Gun Room Press, Highland Park, NJ, 1959

Leech, Arthur B., Irish Riflemen In America, London, 1875

Laidley, Col. T.T.S., A Course Of Instruction In Rifle Firing, Phila, 1879

Marcot, Roy M., Creedmoor And The Remington Rolling Block, American Rifleman Magazine, October 2001

Wingate, Gen. George W. Manual Rifle Practice, New York, 1872