MBA Gyrojet Pistols

by Mel Carpenter

The First Gyrojet, 1962

Robert Mainhardt was not having a great day on Wednesday, October 10, 1962. Mainhardt and his partner, Arthur T. Biehl, Ph.D., had co-founded MBAssociates (MBA) two and a half years earlier on April 1, 1960, and had been working steadily since then, developing miniature rockets designed for the U.S. military as weapons for use in Vietnam. Their first product was a small 3mm-diameter Finjet, which was a type of self-powered flechette similar to the flechettes already being developed under the U.S. Army’s project SALVO and follow-up project SPIW. Those flechettes were steel projectiles loaded into more-or-less conventional cartridge cases and shotgun shells. They were not self-powered. MBA’s Finjets, on the other hand, were powered by internal propellant as self-contained rockets. They were made of light metal or injection-molded thermoplastic, typically Nylon. The final versions had sharp steel penetrators in their noses and were designed to be anti-personnel weapons. They were ignited by pyrotechnic fuses and launched in smoothbore tubes. Finjets were stabilized by fins, like an arrow.

MBA’s second product was the Lancejet, which was essentially a longer, finless Finjet with a heavy nose for stabilization, like a javelin. In early 1962, MBA developed a .25-caliber anti-mine Lancejet under a U.S. Army contract. Although this Lancejet was not adopted by the Army, it led to a wide variety of other Lancejets, some as small as 1.5mm in diameter and others as large as 3mm.

Mainhardt and Biehl understood the need to develop a more conventional, less radical weapon if they were to achieve significant sales to the Army, especially during a time of turmoil with Vietnam heating up and Army Ordnance being split over whether to adopt the new Armalite .223-caliber AR-15 as the M1 Garand’s replacement or the 7.62mm T-44/M14. The Army had about all the controversy it wanted when, in July 1962, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara replaced the Army Ordnance Corps with the Army Materiel Command. MBA needed a weapon to sell that was similar to, but better than, the Model 1911A1 .45 ACP caliber pistol then in use and widely admired by top Army brass and soldiers. MBA had done some earlier experimentation with its third product, the Gyrojet rocket, which was stabilized by angled exhaust ports in its base, or “nozzle,” which caused the rocket to spin like a conventional bullet. Various sizes were developed and tested, and the round settled on as having the best chances of Army adoption was .49 caliber. The rocket used normal double-base propellant and off-the-shelf small pistol primers for ignition.

The problem facing Mainhardt and a few members of his engineering staff at their weekday luncheon meeting at a local restaurant was that the only firearms MBA had for testing the new Gyrojet rockets were modified existing weapons. One of these was a bored-out .38-caliber revolver, which was being used to demonstrate the new .49-caliber rocket. Another type was a modified H&R revolver with its cylinder removed and its barrel replaced with a clear .49-caliber smoothbore tube. These pistols fired Gyrojet rockets the same way they fired conventional cartridges; i.e., the rocket’s primer was struck from behind by the pistol’s firing pin. The test guns’ actions were not changed.

A Gyrojet rocket’s ignition and launch cycle is very slow compared to a regular cartridge. When its primer is struck, it ignites and in turn lights a “second fire” (typically a piece of treated paper or cord) in the center of the rocket’s propellant, which is one piece with a hollow center. The “second fire” igniter helps ensure that the inside of the propellant “grain” (an MBA term for the single piece of propellant, not to be confused with the grain as a unit of weight) ignites evenly lengthwise. The grain is designed to burn only from the inside to the outside. As the grain begins to burn, the rocket begins to develop thrust and move forward, somewhat slowly at first. As a result of this slow acceleration of early experimental Gyrojet rockets in test barrels, it was common for rockets to dribble out of the muzzle, sometimes falling to the ground where full ignition would be achieved with the rocket flying off in random directions, including back at the shooter. This happened twice to Biehl during testing, and it was only by chance that he was not injured or worse.

Sometimes, with a dud or hang fire, the force of the firing pin alone was sufficient to propel the unrestrained rocket out of the barrel. Readers who own a Model 1911A1 type pistol or .38 revolver can demonstrate this effect by first carefully checking to be positive the handgun is unloaded, and then placing a wood pencil with a rubber eraser into the barrel of a cocked gun with the eraser against the breech face where a cartridge’s primer would be. When the trigger is pulled and the hammer rotates forward, it will normally propel the pencil several feet out in front of the gun. The same thing was happening with the early test Gyrojets. There had to be some way to restrain or “hold down” the rocket inside the barrel until enough thrust had been built up for a normal launch at a higher velocity, and nobody at MBA had yet figured out how to do this. Until the problem was solved, the new Gyrojet was going nowhere, and without the Gyrojet, MBA would have to cease operations. Later, the company won a number of significant government contracts, and it significantly diversified its products and services, so the failure of one would not cause the MBA itself to fail.

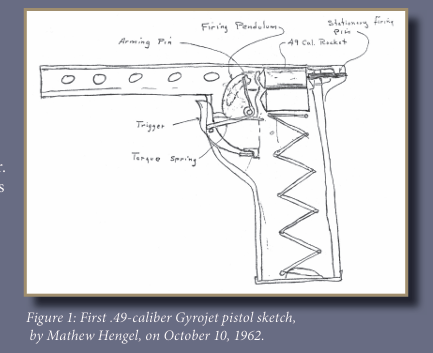

Mainhardt conducted his lunch meetings very informally, with an open exchange of ideas on how problems might be solved. Everyone was encouraged to express their thoughts to the group, no matter how nonsensical they might seem. One of Mainhardt’s new 1962 hires was an engineer named Mathew Hengel, who had been hired to solve a problem with the MBA’s anti-mine Lancejets, which had a nasty tendency to explode as soon as they were fired — they had PETN explosive warheads to destroy mines. Hengel had solved that problem, and he listened carefully as others at the table explained the situation with the Gyrojets not being restrained as ignition began. As the conversation continued into the afternoon, Hengel began doodling on a paper napkin. After a while, he completed the drawing of a new Gyrojet pistol design, shown below in Figure 1.

Although this sketch is crude, it accurately depicts the firing method and hold-down used in every production Gyrojet firearm, which was a fixed firing pin at the rear of the pistol’s chamber and a hammer mounted forward of the rocket. When the trigger is pulled and the sear released, the hammer pivots back to strike the Gyrojet rocket on its nose, pushing it back against the firing pin, which fires its primer. The hammer remains against the Gyrojet’s nose, held there by spring pressure, until the rocket develops enough thrust to briskly move forward, forcing the hammer forward and down and cocking it in the process for firing the next round, pushed up into position by the magazine’s follower spring. Gyrojet rocket ammunition was made with steel cases, normally copper plated, so it could withstand being struck hard on its nose by the pistol’s hammer. Hengel showed the group his drawing and explained his concept. The light dawned, and Mainhardt’s day got a lot better. He authorized Hengel to develop his concept and make a few experimental prototypes.

Hengel worked through October 1962 and into November, when, on November 29, MBA filed patent application 240,784 to protect Hengel’s invention.

Patent 3,212,402 was issued on October 19, 1965, and it lists Hengel as the primary inventor in accordance with Mainhardt’s policy of publicly recognizing his employees’ creativity by having their names attached to patents of their inventions, which were, of course, assigned to MBA. By the time of the patent application, the pistol, not surprisingly, had gone through many modifications and improvements.

Note that the trigger mechanism has been refined somewhat, but that the basic concept of a forward hammer rotating back against the nose of a round of Gyrojet ammunition, pushing it into a fixed firing pin, has been retained. Also note the 6-round internal magazine capacity, which was the actual capacity of every production Gyrojet firearm ever made. Also note the general appearance of the gun compared to the Model 1911. MBA was determined to develop a pistol that looked as much like the M1911 as possible in order to ease the Army’s reluctance to adopt a new pistol. Finally, note the holes in the pistol’s frame around the fixed firing pin to allow exhaust gases to vent outside the pistol, not build up pressure inside the barrel.

A very critical element of the Gyrojet system’s design is that firing the rocket ammunition produces almost zero recoil. All of the high pressure of propellant combustion is contained inside the rocket ammunition, not in the pistol’s barrel. As a result, the gun could be made of lightweight materials, including plastic. In addition, when a round of Gyrojet ammunition is fired, there is nothing left behind to be extracted and ejected. The rocket case itself is the “bullet,” and since the combustion of the propellant is inside the rocket, with most of that occurring outside the pistol, operation of the gun is very cool.

The Model 137.49-Caliber Pistol

The U.S. The Army declined to finance the development of the Gyrojet pistol, probably because it had all of the new technology issues it wanted without adding another, and MBA did not have the required financial resources itself. However, the Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) did have resources to fund high-risk, high-reward projects, including weapons such as MBA’s Gyrojet. ARPA’s first Chief Scientist and co-founder was Dr. Herbert F. York, and York was a friend of Mainhardt and Biehl’s. ARPA’s Project Agile had begun in the spring of 1961 to provide research and engineering funds in support of friendly local forces in remote areas of the world engaged in or threatened by conflict, such as Vietnam. In fact, it was ARPA that provided the first 10 AR-15 rifles to South Vietnamese forces in Saigon for testing.

Project Agile’s timing was perfect for the MBA’s project, and ARPA contracted with the company to develop the Gyrojet pistol and ammunition for use in Vietnam by local officials and rice farmers in defense against the Viet Cong. One important advantage of the Gyrojet was that it would cost less than $4.00 each to manufacture by die casting, and rocket ammunition could be made for about 50 cents each. A simple, lightweight handgun loaded with six rounds of ammunition could be provided for less than $10. The Gyrojet would have zero recoil and twice the impact of a .45 ACP bullet at a distance of 50 feet downrange, and its production by MBA would not interfere with other Army weapons manufacturing.

By late 1962, the first production Gyrojet pistol, the .49-caliber Model 137, had been produced, and it would serve as the model for all future Gyrojet firearms.

The pistol is 9.5 inches long and 5.9 inches high. It was die-cast of an alloy called Zamak, and it weighs 28 ounces, unloaded. The front and rear sights are fixed, and the safety is behind the left grip. The safety is a wedge that slides up in front of the firing pin to block the back of a rocket being pushed back into the firing pin by the hammer. The pistol’s magazine follower can be seen in the loading port above the left grip, and just to the left, the hammer can be seen in its fired position back against the follower. There are holes along the barrel and around the fixed firing pin to allow exhaust gases to vent. The barrel has no rifling or even a smooth liner tube. It just has smooth rails molded in it to guide the Gyrojet rocket. This particular Model 137 is finished in “Jungle Green.”

When Model 137 frames were removed from the mold, a number was hand-stamped in the bottom of the right grip to identify the order in which the frames were cast so mold wear could be checked, and these numbers served as early serial numbers. The highest seen so far is 144, which is the pistol Hengel gave to his daughter.

Model 137 pistols are marked “MBASSOCIATES, SAN RAMON, CALIF.” on the left side under the barrel, and “PAT. APPLIED FOR, MODEL 137 CAL. .49” on the right side. The straight-slot screw in the left frame just above the trigger guard fills a hole left when the full-automatic parts were replaced with semiautomatic ones. The full-automatic capability of Model 137 pistols was quickly dropped early in testing, and existing pistols were modified for semiauto fire only. According to Mainhardt, no full-automatic MBA Gyrojet was ever sold to the Army or on the civilian market. Because of its limited 6-round internal magazine capacity and lack of a quick reloading capability — Gyrojet rockets had to be loaded individually, one by one — select-fire capability was neither practical nor desired.

When I asked Mainhardt why his first pistol was called the Model 137 and not the Model 1, he explained that there was no particular reason for that designation except that it did not indicate that the pistol was MBA’s first firearm. During 1963, production and testing of the Model 137 continued. In June 1963, as the ARPA contract was coming to an end, Model 137 pistols and .49-caliber rocket ammunition were submitted to the H.P. White Laboratory in Street, Maryland, for testing. The tests revealed problems in reliability and accuracy, so modifications to the pistols and ammunition were made. A second series of tests at H.P. White in September 1963 showed that “considerable development effort is still required before this weapon can meet the objective of a low-cost, defensive, hand-held weapon suitable for use by paramilitary or civilian forces.” In addition, when a few early Model 137 pistols were distributed to village chiefs and rice farmers in South Vietnam (VIPs got gold and silver-plated ones) to try out, they were instantly rejected. The last thing the rice farmers wanted was armed conflict with the Viet Cong. As a result of its unsolved reliability and accuracy problems, and its rejection by its intended users, the Model 137 Gyrojet pistol and ammunition’s production ended abruptly. But Mainhardt was not about to abandon his Gyrojets, even though he probably should have. In fact, he was still promoting them when he died in Gilroy, California, on July 3, 2006, at 84 years of age.

The Mark I .49-caliber/13mm Pistol

Mainhardt never threw anything away that could possibly be used later, including Model 137 pistols, which had failed to meet ARPA’s requirements. Mainhardt was also very stubborn, and he refused to drop his Gyrojets simply because he was not able to sell them to the U.S. military. Instead, he turned to the civilian collector, not the shooter market. During a visit to Colt Firearms, Mainhardt had learned of the great success Colt was having selling commemorative examples of its pistols and revolvers, many of which were in fancy wood presentation cases with special finishes, plated dummy cartridges, medallions, and certificates of authenticity. Colt was selling these as quickly as they could be made. In order to maintain their value, these guns were normally not fired, or even cocked, to avoid drag rings around the cylinders. They were carefully maintained in mint condition and enjoyed for their collector interest as special Colt firearms. Mainhardt decided to use Colt’s marketing strategy to sell his Gyrojets to collectors, who presumably would not fire them. Their reliability and accuracy, or lack of it, wouldn’t matter, and MBA could use the revenue and time gained by their sales to continue work developing a reliable and accurate pistol. Some Model 137 pistols were gold-plated, and others were finished in black. Wood grips were added, some with unusual inverted target grips. Lined walnut presentation cases were acquired from the Gerber Knife Company, and 20-round or later 10-round walnut cartridge blocks holding bronze commemorative medallions honoring rocket pioneer Dr. Robert H. Goddard were placed inside the cases. The dummy cartridges were zinc or nickel-plated. Pistols were held in place by walnut blocks inside the trigger guards. Finally, one or two oval brass MBA logos were placed inside the case, and a small brass plate was added to the outside of the case lid to complete the set, which came with a certificate of authenticity printed on an old MBA stock certificate. Mainhardt learned that collectors loved experimental guns, so he had the word “experimental” engraved on some of the guns above the loading port even though they were not really experimental. (Of course, the point could be made that all Gyrojets were experimental.)

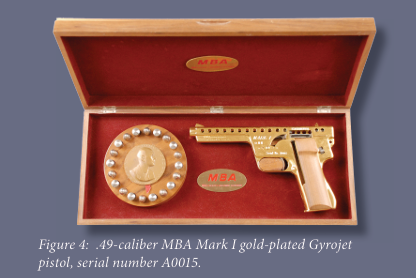

As these sets were being put together, the MBA was working on a new pistol model firing a new rocket. This gun was named the Mark I to differentiate it from the Model 137. However, the Mark I was really just a Model 137 with a number of modifications, some significant. Because the .49-caliber rocket ammunition had reliability and accuracy problems, MBA developed a new 13mm (.51-caliber) rocket with a round nose almost exactly like a .45 ACP bullet. The company also changed its caliber designation from inches to millimeters. Most Mark I pistols are 13mm and have 13mm stainless steel smoothbore tubes inside the barrel frames. The tubes improved the Gyrojet’s accuracy, although Mainhardt was not sure why. It worked, so he used it. Most Mark Is also had a swiveling gate over the loading port on the pistol’s left side to prevent rockets from falling out of the pistol’s chamber, although the pistol shown in Figure 4 does not. At this stage of development and marketing, the MBA was very inconsistent in its markings and characteristics.

During the transition from the .49-caliber Model 137 to the 13mm Mark I, a number of pistols were assembled with characteristics of both types, which was an excellent way to thoroughly confuse current Gyrojet collectors. For example, the 24-carat gold-plated pistol in Figure 4 (serial number A0015) does not have a 13mm barrel liner even though it is marked “13MM” on its left side. In fact, the original “CAL. .49” markings are still in place on the right side under the barrel, and the pistol is .49 caliber. It has no swiveling gate to protect the loading port. Even though it is marked, by engraving, “MARK I,” it is actually just a re-marked Model 137 with walnut target grips installed. It is also marked “EXPERIMENTAL” above its loading port. Half of its 20 nickel-plated dummy cartridges are conical-nose .49-caliber rounds, and the other half are round-nose 13mm rockets.

This pistol’s consecutively serial numbered partner, gold-plated Mark I, serial number A0014, has no caliber markings at all. The “CAL. .49” marking on the right side was ground off before plating. Unlike A0015, A0014 does not have a caliber marking on its left side. The “experimental” pistol has no 13mm barrel tube and is still .49 caliber, even though half of its 10 nickel-plated dummies are 13mm rockets.

Please remember, these guns were for collecting, not shooting. So what if there are no caliber markings, or two different caliber markings? Mainhardt had advertised these cased guns as “the first 1,000 Gyrojets, the rocket guns of the future,” and the extra zeroes in the serial numbers would accommodate up to four digits. Later, when Mark I carbines were developed, MBA decided that the carbines would have four-digit serial numbers and the pistols would have three-digit numbers. I have a matched pair with the Mark I Model B pistol having serial number B022 and the Mark I Model B carbine having serial number B0022. Two authoritative sources, long-time Gyrojet collectors and researchers Eric Davidson of Windsor, Ontario, and David Rachwal of Hilliard, Ohio, believe that a maximum of 100 Mark I Gyrojets were made. Rachwal believes that 85 of these were presentation sets and 15 were carbines, which were basically pistols modified by having longer barrel tubes with rifle walnut stocks added.

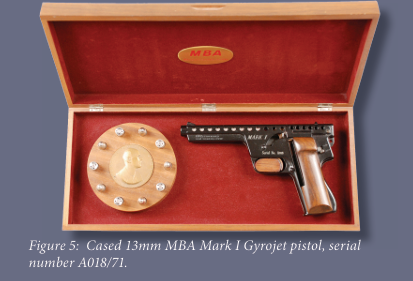

Figure 5 shows what is probably a typical Mark I cased set. It has a black finish, target grips, and 10 nickel-plated, round-nose 13mm Gyrojet rocket dummies. The modified Model 137’s “MODEL 137 CAL.49” markings were ground off prior to finishing, and the pistol’s actual 13mm caliber is not marked anywhere. Apparently, in order to further confuse collectors, MBA left the original Model 137 serial number 71, stamped on the bottom of the pistol’s right butt, in place — most were ground off during modification — and added an extra Mark I serial number A018. The result is a pistol with no caliber markings anywhere and with two different serial numbers.

Thankfully, with only about 100 Mark I guns to deal with, we can move on to the 13mm Mark I Model B, MBA’s most prolific model. Note: I have found no reference in MBA literature, including catalogs or price sheets, to a Mark I Model A firearm, nor have I seen one so marked. However, Mark I guns have serial numbers with “A” prefixes, and are often referred to by collectors as Mark I Model A guns. Since the next model was the Mark I Model B, with “B” serial number prefixes, this doesn’t seem unreasonable.

The Mark I Model B 13mm Pistol

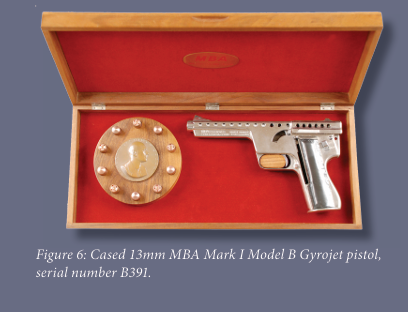

Even though the MBA had lost ARPA’s interest and funding, Mainhardt forged ahead in the development of the new Mark I Model B pistol, which was an entirely new gun made with new dies, not a modified earlier pistol. He was determined to prove that his Gyrojet could be improved enough that the Army would be interested in it. The 13mm Mark I Model B Gyrojet pistol was unveiled at a Las Vegas gun show in September 1965. Its primary “improvement” over the Mark I was a slide that moved back and forward to allow the pistol to be loaded from the top, not from the side. And because the new pistol had a slide for the shooter to manipulate, it was even closer to the Model 1911A1 that Mainhardt was trying to replace. Because so few Mark I guns were sold to civilian collectors, MBA had a supply of walnut presentation cases left over, and Mainhardt decided to again offer his new pistol in cased presentation sets, often with an “antique nickel” finish, cartridge block with 10 dummy Gyrojet rockets, and a Goddard medallion. The grip panels are a marbled silver/black plastic.

Other “standard” Model B pistols were offered with a black finish and plain walnut grips. They were intended for shooting, not just collecting, and were normally packed in flat cardboard boxes.

There are many variations of the Model B, but they all started with the same basic gun. Survival pistols had no wood grips and were equipped with short, sliding barrels to save space. They were intended to be used by downed pilots in self-defense and to launch MBA 13mm distress flares. In some cases, underwater spears for fishing could be fired.

One interesting Model B is from the estate of a CIA employee. It has a matte black finish and an unusual screw-on front sight not seen on any other Gyrojet pistol. The pistol has no markings anywhere and is possibly a prototype designed for clandestine use by agents. Like the survival pistols, its rear sight is a groove cut in the top of the slide.

Approximately 1,100 Mark I Model B firearms were made between 1965 and 1968. Only about 50 were survival or snub nose versions.

The Mark II Model C 12 mm Pistol

The Gun Control Act of 1968, enacted on October 22, 1968, should have ended Gyrojet production. Sales were slow in the civilian market, and in spite of the Army conducting informal tests of the Mark I Model B pistol in Vietnam, probably as a courtesy to Mainhardt, there were no Army sales. The Gun Control Act of 1968 did several things of interest to collectors, and one of them was to designate any firearm with a caliber larger than .50 a destructive device. .50-caliber BMG (Browning Machine Gun) semiauto sniper rifles are “normal” unrestricted firearms because their caliber is not larger than .50 and because their barrels are rifled. Unfortunately for the MBA, 13mm Gyrojet rockets were .51caliber. I have measured hundreds of Gyrojet rockets and discovered that most “13mm” rounds actually measure 12.94mm, which is 0.5094 inch; barely, but clearly larger than 0.5000. And until 1968, all Gyrojet barrels had been smoothbore because rifling was not required to spin the rockets. Collectors and shooters who owned 13mm Gyrojets had a problem, but when they tried to register their guns with the ATF during the one-month amnesty period in November 1968, their forms were returned marked “Registration Not Required.” Obviously, in spite of the Act’s wording, ATF did not consider the guns to be destructive devices. But because of the new law’s wording, the MBA could no longer manufacture 13mm guns with smoothbore barrels.

At first, the MBA offered to convert customers’ guns at no charge by substituting a reduced-caliber 12mm barrel liner for the 13mm one and re-marking the pistols “12mm.” The company did very few of these conversions because most owners simply didn’t bother to send their guns in.

In order to comply with the 1968 law’s requirements, the MBA modified the molds the pistols were cast in, changing the model designation to Mark II Model C 12mm. New rifled stainless steel barrel tubes were used in the new model, although the rifling is very shallow and serves no purpose other than to comply with the law. Gyrojet rockets are not affected by it, and at least one MBA employee conducted a silent protest against the new law, which cost MBA a lot of money, by installing the 12mm rifled barrels backwards so a clockwise-spinning rocket would be fired through a counterclockwise-rifled barrel, with no ill effects at all.

Almost all of the 606 Mark II Model C pistols made were finished in black with plain walnut grips. They looked identical to the Mark I Model B guns, except for the newer markings. pistols “12mm.” The company did very few of these conversions because most owners simply didn’t bother to send their guns in. In order to comply with the 1968 law’s requirements, the MBA modified the molds the pistols were cast in, changing the model designation to Mark II Model C 12mm. New rifled stainless steel barrel tubes were used in the new model, although the rifling is very shallow and serves no purpose other than to comply with the law. Gyrojet rockets are not affected by it, and at least one MBA employee conducted a silent protest against the new law, which cost MBA a lot of money, by installing the 12mm rifled barrels backwards so a clockwise-spinning rocket would be fired through a counterclockwise-rifled barrel, with no ill effects at all. Almost all of the 606 Mark II Model C pistols made were finished in black with plain walnut grips. They looked identical to the Mark I Model B guns, except for the newer markings.

Early in my research, most Gyrojet collectors thought that fewer than 600 Model Cs had been made, so I thought that my number 599 might be the last one. This would have been nice since I also have the first production Gyrojet made, serial number 1. However, I later discovered factory inventory records that showed a Mark II Model C with a serial number of 606. A handful (11) of Model C pistols were gold plated and placed in leftover walnut presentation cases. Some of these have a cartridge block with 10 rounds and the Goddard medallion, but others do not. In the early 1970s, as Mark II Model C Gyrojet production was winding down due to slow sales, Mainhardt thought there might be a market for a cheap derringer-type gun that could fire Gyrojet rockets, regular ammunition, and distress flares. One of these experimental guns was made by modifying a steel German Rohm .38 Special derringer so it could fire 12mm Gyrojet rockets or distress flares from its top barrel and .38 Special rounds from its lower barrel. It was named the “Survival 2000.” The second of these was made by modifying a cast-metal Italian .22 blank starter pistol to fire 12mm Gyrojets from both barrels. It was named “Survival 2001.” Neither of these went to market, and only three or four prototypes of each were made, according to Mainhardt.

Summary

Although exact numbers are not available, it appears that MBA made about 1,900 firearms between 1962 and 1972. These include experimentals, prototypes, Model 137 pistols (45), Mark I pistols converted from Model 137 pistols (100), Mark I Model B pistols (1,100), and Mark II Model C pistols (606). A few Mark I and Mark I Model B pistols were modified as military and sporter models. You will see a Gyrojet census with about 500 different firearms listed by Model, Caliber, Serial Number, etc. The list represents all of the Gyrojets in my collection and other collections, factory records, and guns reported to me. It is a PDF file which can be downloaded, saved, and printed (and hopefully added to). Why didn’t Gyrojet pistols succeed? With very few exceptions, handguns are defensive weapons designed for use at short distances. Because of this, handguns must be powerful at very short ranges, often at distances of just a few feet. Initial high velocity and stopping power at the muzzle are critical. Gyrojets lacked this close-in performance, only achieving their potential at distances of about 50 feet or more. Handguns must be 100% reliable, or they are junk, worse than nothing, with their false sense of security. Unfortunately for the MBA, Gyrojet pistols were never able to achieve the required reliability, although some of them came close. Handguns must be accurate, or accurate enough, and Gyrojet pistol accuracy was never very good. Finally, personal weapons must be at least affordable enough for most potential users to be able to buy them. In 1966, the year after the Mark I Model B was introduced, a presentation model in a walnut case cost $250 retail, which is $1,736 in 2010 dollars. If you were a shooter in 1966, a standard Model B Gyrojet pistol with walnut grips would set you back $165, or $1,145 in 2010 dollars. However, the real deal-buster was the cost of Gyrojet ammunition. In 1966, it cost $1.50 a round ($10.41 in 2010 dollars) retail or you could save a bit by buying a 24-round box for $1.30 a round ($9.02 a round in 2010 dollars). The reason for the high cost was the very low production rate. If Gyrojets had caught on and been produced by the thousands, their cost could have been competitive. But that didn’t happen in spite of Robert Mainhardt’s stubborn promotion of them at MBA and at all of the companies he founded after MBA was acquired by Tracor, Inc. in 1980. He refused to give up on them and as a result, collectors today have a wide variety of unique rocket firearms to learn about and to seek for their collections. 75 carbines.