Colt’s Dragoon Revolvers

By Dick Salzer

Somewhere we read that if you steal data from one source, it’s plagiarism; if you steal from many sources, it’s research. We have created “research” by liberally and unashamedly combining the work done by others along with our own observations and conclusions, starting with our cover photo. (A very similar photo appeared in 1946 in James Serven’s and Carl Metzger’s pioneering tract entitled “Colt Dragoon Pistols”).

During the ensuing half-century plus, many people have added to that early effort – among them, Frank Singer, Bob Whittington, Max Longfield and David Basnett, Dick Salzer, Paul Sorrell, Kirby Howlett, Derek Povah and others. In this article, we will try to walk you through the development and evolution of Colt’s Dragoon Revolver, relying on a composite of information unearthed by those and other writers. We will also provide a comprehensive listing of suggested further reading at the end. If we seem to obsess about serial numbers, it is because they provide a roadmap to the true evolution of the Dragoon series.

The Whitneyville-Walker. The story of the Colt Dragoon must start with a quick review of its famous predecessor, the Colt Whitneyville-Walker. Colt’s first government contract was for 1000 revolvers of a design resulting from a collaboration between Sam Colt and Sam Walker. The gun was as heavy and cumbersome as it was revolutionary — four and a half pounds of iron, brass, and wood, issued in pairs to Dragoon troops during the Mexican War. They were a mixed blessing. They were, however, the best state-of-the-art weapons of their time—and they were extensively used, as the condition of the nearly 225 survivors will testify. The military Whitneyville-Walkers are each marked with a Company letter and an issue number. These markings appear on the barrel lug, frame, cylinder, back strap, and trigger guard. Lesser known is the fact that they were serial numbered as well, having a

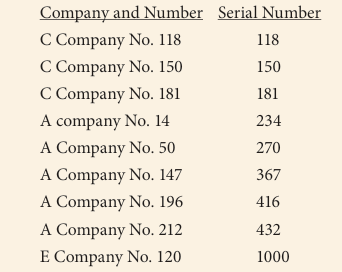

A tiny number is stamped onto the rear of each cylinder. Since the first Whitneyville-Walkers went to Walker’s own regiment, C Company, that’s where the serial numbering on cylinders started. Therefore, the gun bearing the C Company No. 1 marking will have the number 1 on the rear of the cylinder. The following observations from actual guns prove this fact:

The Walker had its design faults, one of which was that the metallurgy of the day didn’t stand up to the size of the charge that could be loaded into the chambers of the cylinder. Consequently, records indicate that many blew out cylinders during proof testing. In one account, a soldier noted that if the bullets were loaded into the cylinder point-first, they were easier to load (this would focus the forces outward and may have caused some of the in-use cylinder casualties). Having examined about a third of surviving Whitneyville-Walkers, we note that both the “Company” stamping and the back of the cylinder serial number are sometimes totally absent on cylinders. These are almost certainly the guns that experienced cylinder blowouts during proofing and subsequently had their cylinders replaced prior to delivery. All 1,000 Whitneyville-Walkers had to have passed proofing and inspection prior to being accepted by the government inspector, so guns damaged during the testing phase required immediate replacement of damaged parts and reproofing. Some early writers have speculated that Colt had to replace the Whitneyville-Walkers that failed in service after delivery with Dragoons, but evidence has been unearthed that proves that conjecture was pure fable. Once the Walkers were accepted by the government, Colt had no continuing liability.

In addition to the military contract pieces, Colt produced 100 extra Whitneyville-Walkers for the commercial market. These were serial numbered 1001 through 1100, a numbering sequence that began there and extended all throughout the Dragoon production period.

The Hartford-Whitneyville Dragoons

At the conclusion of the Walker production, the special equipment, dies, and leftover parts reverted to Colt, who moved them to leased space in nearby Hartford.

The drawbacks of the Walker led to a redesign. The cylinder was shortened, as was the barrel. A more secure catch was designed to hold the loading lever in place, and the locking wedge that secures the barrel to the frame was improved. The weight was reduced by about half a pound. 5 – A slightly later Whitneyville-Hartford Dragoon, showing the square cut frame back, serial No. 1216/

A small number of prototype pistols, the forerunners of the Dragoons, were made by Colt at the new Hartford location. These were based upon some modified surplus or rejected Walker parts as well as new production components. The first of these seems to have used cut-down Walker frames as they retain the circular inset at the juncture of the grip and frame. One gun, bearing a much later serial number, actually has remnants of Walker markings (see Figure 6). Dies and numbering stamps are also listed among the items moved to Hartford. Some of these early production pistols also used the iron backstraps of the Walker design. As the leftover parts were used up, the inset frame feature at the junction with grip quickly gave way to the straight junction used for all subsequent revolvers, and brass backstraps made their first appearance. Those first Dragoons are visually easy to identify as the frame markings are on the right side, and many have a distinctly different profile to the grips (see Figures 3 and 4). Initially, only about 250 of these Hartford Whitneyville pattern dragoons were produced; the highest known serial number for the series is 1337. The survival rate of those few guns is small, and specimens are the most difficult Dragoon variation to acquire.

Colt apparently never discarded anything that had continuing value. Even the distinctive, tiny serial number stamps used on the civilian Walkers were recycled for use on these early dragoons (more about this later).

Before we go on, it is worth mentioning that the Dragoon nomenclature, so familiar to collectors, is a recent invention by collectors for their convenience. With the exception of the Walker model, Colt’s Dragoons were officially known variously as the “Improved Model Holster Pistol” and later as the “Old Model Army Revolver”. In military records, the terms “Colt’s Patent Pistol” and “Colt’s Dragoon Pistol” are also encountered. Terminologies such as first, second, and third models are strictly a collector’s shorthand for delineating the major visible changes during the evolutionary development of these guns.

Having said that, the easiest way to keep the story straight is still to continue to use that shorthand

Dragoon Mass Production- The Second Government Contract

There is a peculiar break in the numbering of early Dragoons. After the completion of the First Government Contract (the Walkers), Colt was awarded a Second Government Contract of 1,000 more guns. For whatever reason, he chose to start numbering these guns at around number 2000 (lowest number noted 2016) and continuing through around 3000 (highest number noted 3012). This led to a chronological gap in the numbering sequence since numbers 1350 (about) through 2000 (about) were temporarily missing. Apparently, at the conclusion of the second contract, he reverted and back-filled the missing serial numbers with civilian guns. This we know for two reasons:

First, the tiny serial number stamps used for civilian Walkers and Hartford-Whitneyville Dragoons were used for the Second Government Contract guns until they wore out, this occurred at around serial 2700. He then began using a slightly larger numbering stamp set through the end of the contract and for the “backfill” guns.

Second, the “backfill” guns exhibit certain subtle characteristics that only emerged at the end of the Second Contract series

Collectors had been confused by this anomaly until Max Longfield and David Bassnett worked out the true story in their now-famous monograph (see Further Reading). One early writer, John Fluck, completely misinterpreted this sequence and wrote a seminal article in American Rifleman Magazine in which he concluded that these tiny numbers and other features indicated that Dragoons in a special serial number range were “replacements” that Colt was forced to supply for Walkers that had “failed in service”. As stated previously, the Walkers, once accepted, were totally the government’s property and responsibility. Although this theory has been conclusively disproven in numerous articles by several authors, some auction houses still persist in offering these pieces as “Fluck Dragoons” or “Walker Replacement Dragoons”.

The Second Contract pistols were specifically ordered to equip the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen, one of only three mounted regiments in the regular U.S. Army.

A thorough study of this Second Government Contract series has been conducted by me, Derek Povah, Philip Boulton, and others. At this writing, nearly 160 of those 1,000 pistols have been located and recorded.

Further Government Contracts

A succession of nine additional military contracts followed:

The Third Contract in 1850 consisted of 1,000 dragoons. These were issued to the 2nd Regiment of Dragoons. These were marked with “US DRAGOONS” in the rolled cylinder engraving, rather than the more common “Model U.S.M.R.” The serial numbers are in the 3600 to 5300 range, interspersed with civilian pistols

A Fourth Contract, issued in 1851, was for 988 guns; serial numbers for that run are in the 5300 to 6700 range. These guns were destined for the other mounted regiment, the 1st Regiment of Dragoons. These, too, were marked with the “US DRAGOONS” legend on the cylinder.

Additional contracts are noted as follows:

5th Contract – 1852 – 2,000 pistols, serial numbers 6700 to 10200*

6th Contract – 1854- 1,000 pistols, serial numbers 10200 to 11600*

7th Contract – 1855- 1,006 pistol, serial numbers 11600 to 13800*

8th Contract – 1856- 376 pistols, serial numbers 15700 to 16400*

9th Contract – 1859- 932 pistols, serial numbers 16400 to 17800*

10th Contract – 1860 -108 pistols, serial numbers 18200 to 18400*

11th Contract- 1861 – 18 pistols, serial numbers above 18900* *approximate

A total of 8,428 Dragoon pistols were purchased by the Federal government between 1848 and 1861.

Assuming a total production of 18,500, the balance was either sold commercially or purchased by state militias. Dragoon pistols with state or unit markings are well known to collectors. Pistols purchased by the State of Massachusetts bear the “MS” stamp on the trigger guard. New Hampshire purchases are stamped “New Hampshire” on the left barrel bolster. A small group of dragoons purchased by an Alabama cavalry company, the “Crocheron Light Dragoons” were stamped “C.L.DRAGOONS” on the left barrel bevel.

It may be assumed that the balance of production was considered commercial, even though many obviously commercial pistols bear the “US” marking on the frame.

Normally, military issue guns did not have silver-plated brass trigger guards and had oil-finished grips, while civilian guns had brass parts, silver-plated and varnished grips.

As production progressed, a series of evolutionary improvements took place, much to the delight of modern collectors.

The “square-backed” trigger guards gave way to the rounded types at around serial number 10500, the oval cylinder stops of early production were abandoned for rectangular stops around serial number 8000, and the lever catch was modified to a flat design at around serial number 13000. (These numbers are approximated as there is considerable overlap at each transition.)

A number of late production Dragoons were fitted with shoulder stocks and rear sights.

One of the odd and inexplicable changes that occurred during late production was increasing barrel length to 8 inches. These start being seen around serial number 18500 and continue through the highest-numbered Dragoon yet observed—serial number 19645. Dragoon pistols were also produced in the United Kingdom using a separate serial number range.