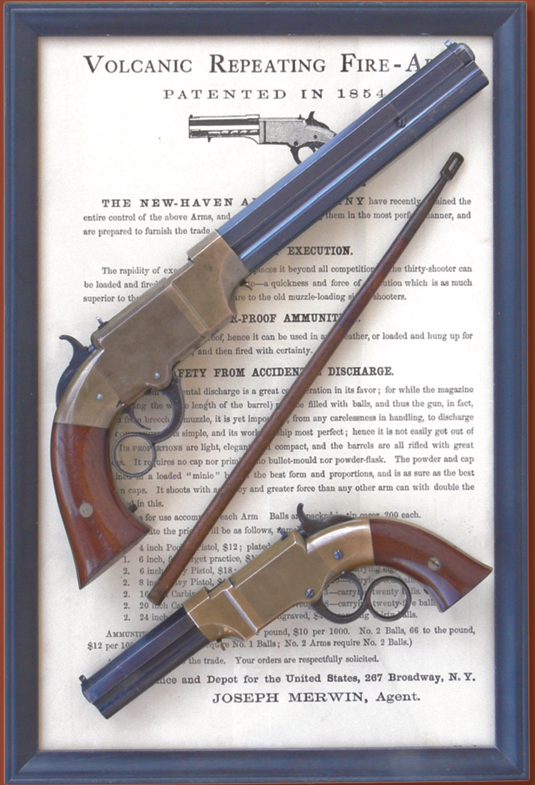

VOLCANIC SELF-CONTAINED AMMUNITION (A Cartridge Hound Special)

By Ed Lewis

The history of the development of the Volcanic firearms parallels the history of the ammunition that was produced to fire in these guns, a history that was to be fraught with unrealized expectations, poor performance, and, ultimately, failure. As we have seen, the story begins with the development of Walter Hunt’s Rocket Ball, a loaded bullet, U.S. Patent No. 5,701, issued on August 10, 1848. The tale winds its way through the largely unsuccessful early attempts to develop a self-contained metallic cartridge for use in the Smith & Wesson pistols and ends with the final form of the Volcanic cartridge.

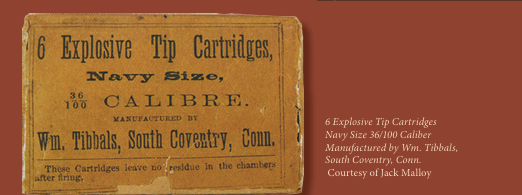

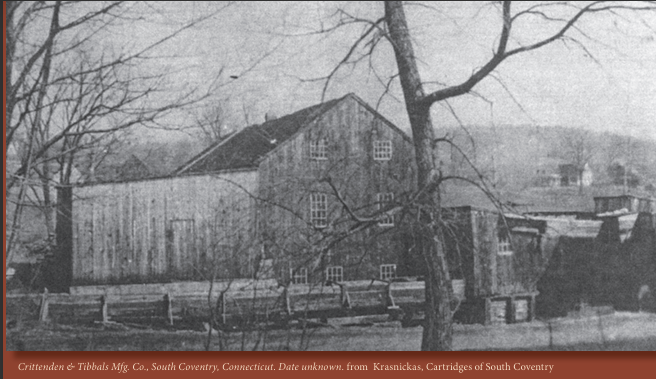

Crittenden & Tibbals of South Coventry, Connecticut, was the leading cartridge maker in the United States during the years that the Volition Repeater, and the later Jennings, Smith-Jennings, and Smith & Wesson lever action pistols were being produced. The first record found of a sale by the company was an invoice to Samuel Colt for percussion caps dated February 5, 1849, through June 15, 1849, for 82,000 caps at a cost of $54.00. No ledger entries or other records survive mentioning their association with companies that produced the Volcanic firearms. They are, however, thought to have been the first manufacturer of ammunition for the Smith & Wesson Volcanic pistols, and they also later made some of the cartridges for the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company. The following is a brief summary of each of the individuals involved with this very influential company.

RALPH CRITTENDEN

Ralph Crittenden was born in Portland, Connecticut, in January of 1820 and, in his boyhood, moved to South Coventry, Connecticut. After serving as an apprentice in a machinist’s shop for some years, he joined with William Tibbals in the manufacturing of percussion caps. Though he only filed an application for a U.S. Patent, he is said to be the first to put into practical operation a combination of the percussion cap and the rifle ball, a combination which later developed into the more modern cartridges. He later failed to follow through in the process of patenting his invention. He represented South Coventry in the State Legislature of 1856 and 1863, and in 1865, after selling the firm to Schuyler, Hartley & Graham of New York City, he moved to Hartford, Connecticut, where he later died on July 17, 1901.

WILLIAM TIBBALS

William Tibbals was born in South Coventry in December of 1823. He partnered with Ralph Crittenden to form their very successful company. After the Civil War, following the sale of their firm, Tibbals stayed in South Coventry for a few years and later also moved to Hartford, where he died on September 17, 1890. He remained interested in cartridge development and was granted six U.S.

THE HUNT ROCKET BALL

It is difficult to understand how the complex Volition Repeater could have been conceived in the mind of the inventor, with such little emphasis given to an effective cartridge. Hunt clearly refused to recognize, or was unaware of, previous self-contained cartridge developments. His self-contained Rocket Ball was a highly inefficient cartridge that was the form of ammunition to be used not only in his new gun but the later Lewis Jennings improvement and the Smith Jennings repeating rifle. Ultimately, the results were disastrous. The Hunt and Jennings repeaters were never produced in any numbers. Many Jennings single-shot breech loaders were converted to single-shot muzzleloaders. The Smith-Jennings repeating rifle was a failure because of the lack of firepower due to escaping gases and the absence of a priming device within the cartridge itself.

Crittenden & Tibbals had expanded their percussion cap production to include the loading of Hunt’s cartridge, based upon his U.S. Patent No. 5,701, issued August 10, 1848, and reissued on February 26, 1850.

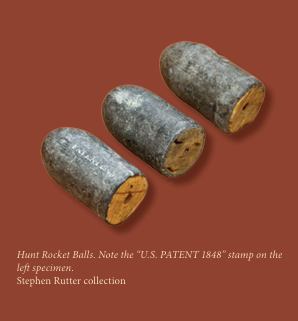

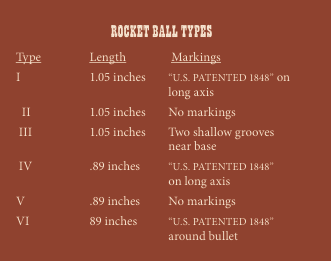

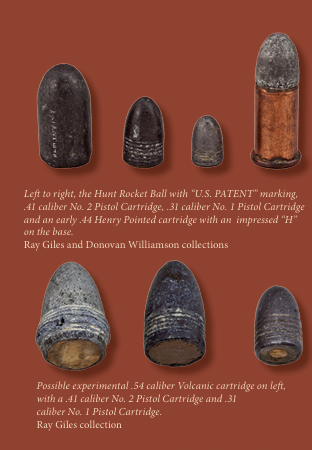

The Rocket Ball was a conical lead bullet with a cavity at the base filled with gunpowder. With the bullet in a mold, the gunpowder was pressed into the hollow and closed by a cork disc that had an ignition hole in the center. Though Hunt’s U.S. Patent called for a metallic disk, only disks made of cork have been noted. It had no primer and required ignition from an external source, a gravity-fed priming pill from the gun’s priming magazine located on the top of the receiver. Detonation by the firing pin caused fire to enter the hole at the base of the cartridge that then ignited the black powder. Some of the later Jennings and Smith-Jennings single-shot breech-loading rifles were built to use percussion caps in place of the pill primer mechanism, which, when struck by the modified hammer, ignited the powder. The original Rocket Ball was .54 caliber and varied in weight from 330 to 336 grains. The weight of the black powder charge is unknown, but suffice it to say that the cartridge was significantly underpowered and the usual muzzleloader, with more powder per weight of ball, far better served the rifleman of the day. The Rocket Ball varied from .553 to .560 in caliber, and at least six variations have been identified among surviving specimens. On some of the cartridges, “U.S. PATENTED 1848” is stamped on the side.

Walter Hunt gave no consideration to grease grooves and had no knowledge of their value. Richard Lawrence, of the Robbins & Lawrence Company, Windsor, Vermont, had developed the use of lubricating grooves to both improve accuracy and to help prevent barrel fouling. Courtlandt Palmer, the financial backer of the Jennings and Smith-Jennings rifles, had directed Lawrence to demonstrate the new Jennings repeater to a prospective foreign buyer. After almost a full day of inaccurate firing, resulting in an excessively fouled barrel, Lawrence came upon the idea of grease grooves, as the breech-loaded bullet used no greased patch like a muzzleloader bullet did. He cut several grooves in each of the Rocket Balls to be used during the second day and filled the grooves with tallow. The second demonstration of the Jennings repeater resulted in much greater accuracy with a clean barrel. Although experimental, his innovation proved to be successful ,and some Rocket Balls are found with two grooves near the base for a lubricant. In theory, this also permitted a bullet to more easily enter a fouled chamber. The skirt of the cartridge had to be made thinner to allow expansion to seal the bore against forward gas escape. Examples of this cartridge are scarce, and no boxes of the cartridge are known to have survived. A modification of the Rocket Ball would later be chosen by Smith and Wesson for use in their lever-action repeating pistols.

THE SMITH & WESSON METALLIC CARTRIDGE EXPERIMENTATIONS

Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson were familiar with the Flobert cartridge, which was essentially a small round ball inserted into the end of a percussion cap. It was developed by Louis Nicholas Auguste Flobert and designed for indoor target use in a “Saloon Pistol”, literally pistolet de salon, a practice pistol for Paris gallants for the deadly business of defending one’s honor, or that of one’s lady. In reality, it was little more than a toy. Wesson had purchased a supply of balls and percussion caps from Crittenden & Tibbals for experimentation and later patented a Flobert-style single-shot pistol in 1851 or 1852.

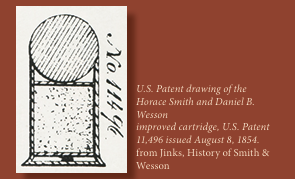

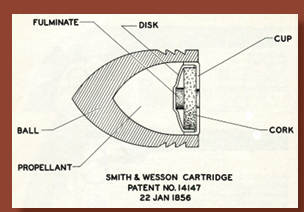

Smith and Wesson realized that the success of their lever-action repeating pistol depended on a more suitable self-contained metallic cartridge. To this end, they applied for a U.S. Patent for such a cartridge on May 10, 1853. The patent covered the feature of a priming compound coating the inside of the base of the metallic case, separated from the powder by a perforated metallic disc. On top of this disc, the powder charge was separated by a solid partition from the ball in the open end of the case. The shallow cup formed between the powder partition and the ball was filled with tallow. After some delay due to possible infringements on Flobert’s cartridge patent, U.S. Patent No. 11,496 was finally granted to Smith and Wesson on August 8, 1854.

Smith and Wesson clearly had a metallic cartridge in mind for their U.S. Patent No. 10,535 issued Feb. 14, 1854, for a magazine firearm. In mind for in their U.S. Patent No. 10,535 issued Feb. 14, 1854, for a magazine firearm. The U.S. Patent application drawing illustrated the configuration of this type of cartridge rather than the standard loaded ball cartridge generally associated with this style of firearm and this claim of novelty may be found: “….the improvement of making the front end of the piston slide with a dove-tailed recess, or its equivalent, for the purpose of enabling the slide to seize the metal of the cartridge ……and so that the refuse metal or cartridge may be withdrawn from the barrel….” This metallic cartridge was never produced in quantity because, in the early 1850s, little was known about the annealing and drawing techniques for copper. Due to the lack of this knowledge, it was virtually impossible to form copper without cracks and tension tears. Some, however, were produced since several prototype or experimental rifles were chambered for a self-contained metallic-cased cartridge in .50 caliber. Still faced with the necessity of developing ammunition for their new lever-action pistol, they reverted to a modified form of Hunt’s Rocket Ball. The same deficiencies of Hunt’s cartridge would continue to plague the modified rounds. They were used in all subsequent Smith & Wesson and Volcanic Repeating Arms Company guns and were known as the Smith & Wesson No.1 or No. 2 Pistol Cartridge. This Smith & Wesson volcanic ammunition is not to be confused with their later No. 1 (.22 caliber) and No. 2 (.32 caliber) metallic rimfire cartridges fired in their Model 1 and Model 2 revolvers. The decision to use these underpowered cartridges spelled the demise of not only the first Smith & Wesson Company but also its successor, the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company

THE SMITH & WESSON “VOLCANIC” CARTRIDGES

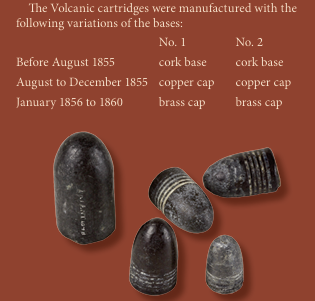

The Smith & Wesson No. 1, a .31 caliber cartridge, was made for use in the small frame pistols, and the Smith & Wesson No. 2, a .41 caliber cartridge, was made for use in the large frame pistols. These cylindro-conoidal-shaped cartridges have also become known as the Volcanic No. 1 Pistol Cartridge and the Volcanic No. 2 Pistol Cartridge. The construction of the two cartridges differed only in caliber, and although some variation is found in the diameter of both the .31 caliber and the .41 caliber cartridges, these caliber designations are generally accepted by collectors. Some later Volcanic cartridges have been found with a .36 bullet diameter. No gun is known that will chamber this cartridge. The History of Winchester by Charles T. Haven mentions that “A.. .38 caliber Volcanic bullet was recently dissected in the Winchester Laboratories and found to contain a powder charge of 6 ½ grains plus a small priming pellet of fulminate of mercury and glass in the base of a 100 grain bullet”.

As originally made, the bullet was first charged with black powder, then an iron anvil disc was placed, followed by a fulminate priming pill over which a cork base was placed. The bullet was closed at the rear by pressing the lead inward against the cork. Later, a perforated metal cap was sometimes used to cover the cork. After assembly, the ball was grooved and greased, swaged and varnished.

Earlier mention was made of the grooves made near the base of the bullet in some of the Rocket Ball cartridges, and these were continued in the construction of the Volcanic cartridges, where two styles of grooves are found on the conventional Volcanic cartridges. One style, which is suspected of being the earlier of the two, has five or six fine grooves. The other style, thought to have been used later, has only three or four rather coarse grooves. The reason the finely grooved type is suspected of being the earlier is that almost all finely grooved specimens examined have iron anvils, while the majority of the coarsely grooved Volcanic cartridges examined employ a brass anvil.

Copper caps proved unsatisfactory because of faulty extraction and are very rare. Thereafter, brass was used to facilitate extraction. The brass anvil was a decided improvement over the iron anvil because iron has a habit of reacting unfavorably with fulminate over time, rendering the primer inactive. The manufacturers of the Volcanic cartridge must have discovered this and switched from iron to brass shortly after they instituted the coarse grooving. Just when this happened is a matter of conjecture, but a good guess would be in the late 1850s. The United States Ordinance Department made the same discovery several years after the Civil War when it permanently discontinued the manufacture of all anvil types made of iron.

It has been said that the poor performance of the .31 caliber round led Smith & Wesson to develop a larger .41 caliber cartridge which was used in the large frame Smith & Wesson pistols and, with modifications of the priming mechanism, in the large frame pistols of the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company and the later large and small frame pistols and carbines of the New Haven Arms Company. The No. 2 Pistol Cartridge had a black powder charge of 6.5 grains in a 100-grain projectile, which generated a muzzle velocity of only 260 feet per second. This was a less-than-ideal performance. Even the short rimfire cartridge of the 1863 Derringer was more powerful. With its 13 grains of powder in a 130-grain projectile, the muzzle velocity of the Derringer was 520 feet per second. The performance of the No. 1 Pistol Cartridge was even less satisfactory. One anecdotal story about the performance of the .31 caliber Pocket Pistol was related by Allan Kelley, a well-known gun dealer from New Haven. A despondent gentleman sat on his door stoop one evening after his family left him alone while they ran errands. The man decided to depart this world and shot himself several times in the temple with his pistol, presumably working the lever for each shot. His family returned to find him bloodied but alive with the gun still in his hand. Afterwards, the pistol and remaining ammunition were sold by the family to Kelley.

Crittenden & Tibbals of South Coventry, Connecticut, were the first manufacturers of the .31 caliber and .41 caliber Smith & Wesson Volcanic cartridges. On July 10, 1855, the assets of the partnership of Smith & Wesson became the sole property of The Volcanic Repeating Arms Company. When Oliver F. Winchester bought the assets of the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, he acquired the rights to the Smith & Wesson ammunition patents and all future improvements derived from them. The Ammunition Department of the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company was later established on May 1, 1856, with four female workers, transferred from the Gun Department, working under the direction of M. L. Babcock as foreman. Previously, the ammunition had come from Norwich and South Coventry. By 1856, there were seven women employed in the shop. At the time, Crittenden & Tibbals still provided the primers. On August 26, 1864, Crittenden & Tibbals sold all of their holdings to Jacob R. Schuyler, Marcellus Hartley, and Malcolm Graham of New York City, and the firm became the Union Metallic Cartridge & Cap Company. A list of the transferred assets included “two sets of machinery for Volcanic Arms”.

As long as it remained in stock, the Volcanic ammunition continued to be sold to military goods dealers and gun owners. However, on September 3, 1863, the New Haven Arms Company replied to Tryon & Brothers of Philadelphia: “… we are entirely out of No. 1 Balls and it is uncertain how soon we shall have any more, as the parties who made them have changed their machinery for other purposes. As soon as we can succeed in getting any, we will inform you”.

PROBLEMS WITH THE CARTRIDGES

With care, comparatively little trouble was experienced with the Volcanic cartridges. There are records of over one hundred consecutive shots with a Volcanic carbine before any difficulties were encountered. Such a performance was a wonder. In the day of these arms, when muzzleloaders were standard, B. Tyler Henry, who was probably in charge of the production of the Volcanic pistols, testified that he never experienced trouble with misfires in his job of personally test-firing every one made. In a later chapter, we will find that some individuals preferred them to Colt’s pistol. That said, there were some serious drawbacks to the cartridges. While the self-contained ammunition was relatively waterproof and easier to carry than loose powder, balls, and caps, these advantages were offset by its many problems. They were underpowered, and the claims of long range and excellent accuracy were overblown. The small hollowed-out bullet could not hold a sufficient amount of powder to achieve significant velocity. There was always a possibility of the discharge of cartridges in the magazine should undue pressure be exerted on the thinly protected priming charges in the base of each bullet. There was also the usual fault of all breech-loading guns before the advent of the metallic cartridge. The bullet had no effective shoulder and was incapable of sealing the breech on detonation, thus causing a leakage of gas. The balls were sometimes oversized and would not enter the chamber, but would discharge with pressure from the bolt with unexpected and undesirable consequences. Sometimes an undersized cartridge would be pushed too far into the chamber and would not fire, requiring removal with a rod, as was prominently mentioned on the cartridge box label. Increasing the friction between the cartridge and the walls of the chamber to prevent this resulted in another problem: “thimbling”, where the head of the ball would exit the barrel but leave the rear portion of the bullet lodged within the chamber. Another common problem was the incomplete extraction of the priming disc, leaving a portion in the chamber and rendering the arm inoperable since a new round could not be loaded. At least with one of Colt’s percussion revolvers, if one charge failed, you could go on to the next. Lastly, the priming fulminate often caused corrosion of the firing pin, requiring its replacement.

The many problems with the ammunition contributed to poor sales and the bankruptcy of the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, and later, when the same ammunition was used in the firearms of the New Haven Arms Company, it endangered that company as well. A better cartridge was clearly needed. The ammunition problem would finally be solved when B. Tyler Henry developed his metallic .44 rimfire cartridge, thus assuring the success of the company.

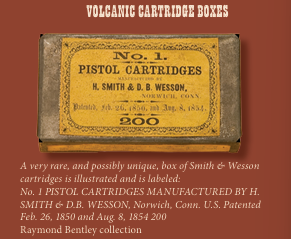

The U.S. Patent date of February 26, 1850 is for the reissue of Hunt’s U.S. Patent No. 5,701 for “IMPROVEMENT IN METALLIC CARTRIDGES” while August 8, 1854 is the date of Smith and Wesson’s “IMPROVEMENT IN CARTRIDGES”, U.S. Patent No. 11,496, for the metallic cartridge that was never produced. The gray, non-lacquered tin boxes held 200 Volcanic No. 1 Pistol Cartridges and were probably produced by Crittenden & Tibbals despite the claim of manufacture by Smith & Wesson.

Although the ammunition for these firearms was most likely manufactured by Crittenden & Tibbals, there are no known Volcanic cartridge boxes bearing their name. The cartridges, whether of .31 or .41 caliber, were packed two hundred to the box, and sawdust was sometimes used as filler between the rounds.

The earliest and most commonly found boxes, probably produced by the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, were made of black japanned tin, which was then lacquered. The label on this style of box is found in varying shades of off-white or buff and was pasted on the inside of the lid. Later, cardboard boxes were manufactured by the company and are extremely rare, probably due to their fragility and, with the Volcanic firearms becoming obsolete, decreased production. They have a green label pasted on the top of the box, and the lettering style and borders resemble boxes later produced for the Henry Rifle.

One author has stated that “The cartridges came in round tins holding 200 each, which sold for $10 and $12 per thousand”. Though numerous inquiries have been made, no one seems to have seen a round tin, but a pistol case is known with two round compartments that could have held such tins. The cardboard boxes were most likely produced by the Kingsbury Box Company of South Coventry, which was located very near the Crittenden & Tibbals Company.

Several individuals have related stories of dealers and collectors who have sold individual cartridges from full boxes and, when the box was empty, to the chagrin of collectors, simply discarded the box. This is perhaps one of the major reasons why Smith & Wesson boxes are unknown and Volcanic tin boxes are rare. Boxes of the Hunt Rocket Balls are unknown but if one is found it would most likely have a Crittenden & Tibbals label. Virtually unknown, and Volcanic tin boxes are rare. The boxes of the Hunt Rocket Balls are unknown, but if one is found, it would most likely have a Crittenden & Tibbals label.