Armed Images: Part 1

By: Frank Groves

Antique photographs of people have always been of interest to this writer in large part because these early images capture those persons’ actual appearance, dressed in the true garb of the period, as opposed to the interpretation placed on such details in modern movies and television shows that may, or more likely may not, be historically accurate. We see many settings chosen by the subjects and can easily surmise the reasons that they considered important enough for them to pay a photographer to capture their image.

There are instances of occupational images that the subjects wished to send to someone dear to them in which they held a tool, a gold mining pick, a musical instrument, a bible, or other similar items that associated them with a particular profession or calling. One of the most interesting and relatively rare early photographs is that involving firearms. These images offer a very interesting “snapshot in time” showing people dressed in authentic clothing, and with weapons that are in very fine to new condition during their period of use.

Before we go too far, a brief history of early photographs is in order. The earliest successful type of photograph was the daguerreotype, initially perfected by Frenchman Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre in 1839. His method consisted of treating silver-plated copper sheets with iodine to make them sensitive to light, then exposing them in a very rudimentary wooden camera and “developing” the images with warm mercury vapor, which was very dangerous to the photographer. The process became very popular in America by 1843, and a portrait industry was born. These early photographs were relatively expensive, ranging from $2.00 to $5.00 each.

By the late 1850s, the next process perfected was known as the ambrotype. This was a similar process to the daguerreotype, whereby an image was deposited on the back side of a glass plate that had been treated with an emulsion. It was cheaper and favored because it did not have the very reflective appearance of the daguerreotype, which is hard to view directly due to its mirror-like surface.

Following that, for a very short time, was a process called the melainotype, which was basically an ambrotype process, but instead of a glass plate, the image was deposited on the front side of a tin plate. This quickly evolved into the tintype, where a more direct photograph was put on the front side of a metal plate. These first three processes had usual sizes of ninth plate, sixth plate, quarter plate, half plate, or full plate, along with the much smaller 1/16th plate, and “gem,” which was about the size of a postage stamp. A photographic “plate” inserted into the camera measured 6-1/2” x 8-1/2”, and the photographer could set his lens to use the full plate or a portion thereof to lower the cost for himself and his customer. Without going into a lot of detail on sizes, the most commonly seen sixth plate will have an outside dimension of each side of the case of about 3-1/8” in width and 3-5/8” in height.

The final process that we are looking at here is the Carte de Visite, also known as the CDV, where an albumen process was used to create a negative from which any number of prints could be made and put onto a thin piece of cardboard. These images were less varied in size, and most had their own size known as “CDV size” that measured about 2-1/8” by 3-1/2” mounted on a card measuring 2-1/2” by 4 inches. CDVs were the first process wherein duplicate images could be made simultaneously. Prior to that, all photographic images were singular and unique. CDVs were popular from the mid-1860s to the 1870s.

Due to the control of lighting and setting since an exposure was so long, most images were taken in a studio of sorts and will usually have a painted background behind the subject to suggest that the image was taken outdoors. Some were done this way by traveling photographers, but most were done in the studio.

How to quickly tell the difference in types? A daguerreotype will look very much like a mirror, and you really cannot see it very well looking straight at it. It needs to be viewed at an angle or with a dark paper above it to reverse the reflection. An ambrotype will feel heavier as it is printed on glass and has an additional piece of glass in front of it when in its cardboard or gutta-percha case. If taken from the case and held up to a light source, it may appear reddish in tint, and some light will come through it. The melainotype on metal looks very much like the later tintype, but the image will be less defined and have more tan or sepia in the color. The tintype will usually be clear, very well defined, and likely will have less of a “halo” effect than the previous ones will get over time. As the tintype process was less costly, the majority of these early images will be tintypes.

Many times daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, melainotypes and tintypes will be “tinted” usually with gold paint on the buttons, but sometimes on several things in the image. Sometimes this will hide detail, especially if this paint is slathered all over the gun or knife, which reduces desirability and value. Sometimes the faces will have coloring to make them more lifelike, and a few photographers did this very well.

All daguerreotypes and ambrotypes will be housed in hinged cases made either of wood that was covered with thin embossed leather or made of hard rubber, also referred to as gutta-percha. Melainotypes are usually in a single frame of gutta-percha unique to these images, and they are relatively rare. Tintypes could either be in leather covered cases or in simple paper slip covers that the image would slide into. CDVs were printed on slightly glossy paper and then glued to their own cards that may have the name and address of the photographer on the front bottom margin or on the back. Sometimes they were housed in a hinged case that is referred to as “CDV sized” as they are longer than those usually seen in sixth plate cases.

As with all collectibles, condition is of great importance. If the image is scratched from cleaning, which is very easy to do, the value will be diminished significantly. Disassembling and just touching the image of any image, with the possible exception of the tintype, will almost always cause irreversible damage.

If you find one and the inside of the glass protecting the image is dusty, it is always best, if you insist on cleaning it, to have someone knowledgeable do this for you.

The following are several examples of armed images that have particular interest. If any image is identified as the person pictured in it, it is much more desirable and valuable. If the firearm pictured is a rare one, that also adds to value and interest. But even showing an average firearm, an armed image is much more valuable than one just showing an unidentified unarmed person from the past. The more prominently the person is holding his weapon, the better it is. I should say here that occasionally – very occasionally – a female is seen armed and pictured, but these are very rare.

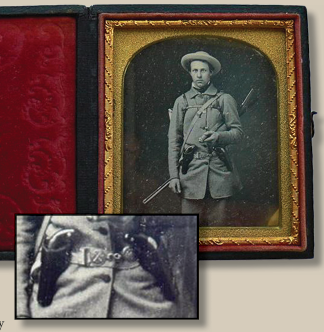

Daguerreotype, sixth plate in a leather-covered case of a man equipped with a Model 1832 Ames Artillery Short Sword, a shotgun slung across his back, and a pair of pepperbox pistols (probably made in the early to mid-1840s) in their holsters on his belt. The belt and buckle for the short sword are properly regulated and likely indicate that he is a former soldier from the Mexican War who is possibly headed for the gold fields or some adventure where he needs to be prepared. The image is very clear. Armed daguerreotypes are by far the rarest of all of the early images. Circa 1840-50.

Daguerreotype, sixth plate image of a very dapper gentleman holding a Fourth Model Ehlers Colt Paterson revolver. The image is very clear, slightly tinted, and shows one of the least seldom seen of armed images – one with a Paterson Colt revolver made about 1840. Another very rare early armed daguerreotype. Circa 1840-50. Courtesy The Colt Paterson Book.

Ambrotype, sixth plate in a leather-covered case of a sergeant with two Colt Model 1849 Pocket models in his belt, along with a stag or horn-handled Bowie knife. His buttons and inlay on his knife are gold-tinted. This image came from the San Antonio, Texas estate of the family of a long line of military men, but the sellers were unsure of this soldier’s identity. Circa 1855-60.

Ambrotype, sixth plate in a leather-covered case of a man holding an over/under percussion rifle. The image is a little dark, but particularly clear, and one can see the inlays in the stock. Reflections from the rifle show that it is brand new at the time. Circa 1855-60.Ambrotype, ninth plate in a gutta-percha case, of a soldier, probably from some militia prior to the Civil War, prominently holding a pepperbox pistol. The image is particularly clear. Circa 1855-60

Melainotype, sixth plate, of a soldier (sergeant) with a Volcanic Pocket pistol in his belt, with a sword in his hand and its scabbard at his side. Buttons and buckles are tinted gold. Very few images with a Volcanic pistol are known. These melainotypes, for the very short time that they were made, are usually accompanied by a hard rubber or gutta-percha frame such as this example. Circa 1858-59.

Tintype, sixth plate in a leather-covered case, of a soldier holding a musket with a Colt Paterson #5 Ehlers revolver stuck in his belt. Images with Paterson revolvers are very rare. Circa 1860-65. Courtesy Dennis LeVett.

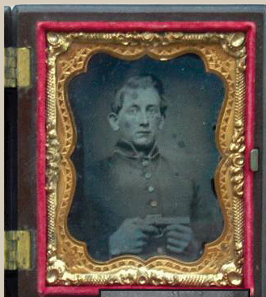

Tintype, ninth plate in a leather-covered case, of a soldier holding a Colt Model 1849 Pocket Model. His buttons are gold-tinted. The reflections and contrasts of the finish of the revolver show that it is brand new. Circa 1860-65

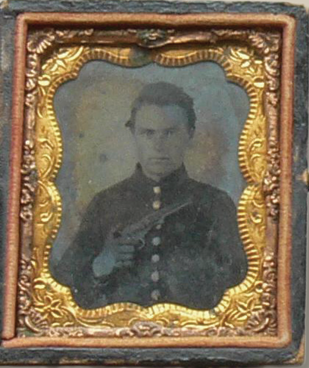

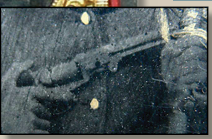

Tintype, ninth plate in a leather-covered case, of a soldier holding a Colt Model 1851 Navy revolver and a sword. The sword hilt and its buttons are tinted gold. The pillow in the case lid is marked with the name George Mather. There were several soldiers with this name who served in the Union Army as well as the Confederacy. Circa 1860-65. These few examples of armed images make for very interesting “go withs” to complement a gun collection and enable us to envision the first owners of these guns, who actually used them. Images are from the collection of the writer unless noted otherwise.

To be continued.