The Tool Room at Colt’s Factory – 1872

Before we get into this story, we have to warn the reader that there is more than a little conjecture involved. The year was 1872. Rollin White’s patent, as assigned to Smith and Wesson, had just expired, and dozens of companies were waiting in the wings to capitalize on the opening of the previously restricted market.

Colt had just come out with their first true cartridge revolver, the Model 1872 Open-Top. That the gun was patterned on previous percussion designs was no accident. Lots of leftover parts remained, and they saw an opportunity to unload frames, backstraps, trigger guards, hammers, and internal parts on their warmed-over offering. It was clear the much-improved Model 1873 Single Action Army was well into pre-production when they put the open-tops on the market.

There was also a lot of unsold inventory of percussion pistols. The market had about dried up for percussion guns—what to do? Convert them to cartridge of course! The standard Richards and Richard-Mason conversions are well-known answers to that dilemma.

Less well-known are some of the tool room experiments that may have preceded those standard conversions.

It’s not hard to imagine that management handed a few percussion pistols to the tool room mechanics and told them to see what they could come up with. Three such guns have surfaced. Each exhibits features that later found their way into production guns, none have been noted in other than the specimens shown.

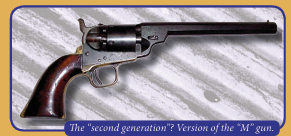

The first was obviously created from a series of random parts. There are no serial numbers on any part—only the letter “M” for “Model” on the frame. The frame also bears the two line marking “PAT. JULY 21, 1871 and PAT. JULY 2, 1872”, thereby placing the date of experimentation after that latter date. This gun was purchased from the Colt factory by Val Forgett of Navy Arms as a potential model for reproduction, but the project was abandoned.

The rammer aperture has been plugged, and the barrel bolster re-machined. The cylinder has been shortened, and chambers machined for cartridge rims. A spacer plate has been added. Inside the spacer plate is a rebounding firing pin for centerfire cartridges. A loading channel has been machined on the right recoil shield. The brass backstrap and trigger guard base have been drilled and tapped, perhaps for some sort of shoulder stock. All in all, it’s a pretty basic series of modifications.

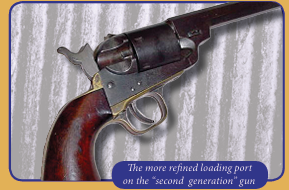

The next piece seems to be a refinement of the previous conversion. This one was based on a surplus gun—serial number 99967. It is also a refugee from the Colt Co. archives. The rammer aperture has been plugged, and the barrel bolster re-machined with a slightly different contour than the previous gun. The cylinder has been shortened and chambers machined for cartridge rims. The spacer plate in this case is more elaborate with a rear sight reminiscent of the rear barrel sight on the model 1872 open-top. Again, a rebounding firing pin for centerfire cartridges. The loading groove is more neatly executed. (This gun and Colt’s Tool Room are further discussed in Bruce McDowell’s book under Further Reading)

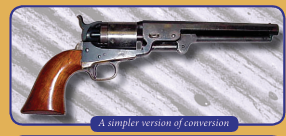

The final example is based upon a near mint surplus gun—serial number 36820. It is the simplest of all. The cylinder was shortened and chambers machined for cartridge rims. A spacer plate with a hinged gate was installed. The hammer was modified with a firing pin extension for centerfire cartridges. If I were to guess, I’d guess this experment may have preceeded the above versions.

It would be extremely interesting to learn whether more examples of this transitory period in Colt’s history exist. If you have one, let us know.

Further Reading:

Adler, Dennis, Metallic Colt Conversions, Krause, 2002

McDowell, R. Bruce, A Study Of Colt Conversions And Other Percussion Pistols, Krause, 1997