Patents – Circumventions and Infringements

The Rollin White Patent and Its Impact on the Firearms Industry

Seventeen years is a long time to wait, especially when you’re watching the hottest arms market in history pass you by. That was the plight of almost all arms makers during the period from 1855 through 1872 when competing gun manufacturers were enjoined by patent restrictions from producing the latest revolvers. How could they manage to capitalize on that fast-escaping market? Here’s what happened and what they did.

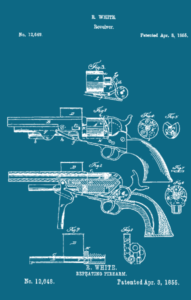

The Birth of the Bored-Through Cylinder

In 1855, Rollin White was issued a U.S. patent (No. 12649) for an extremely complex and impractical pistol featuring a cylinder that was automatically reloaded from a vertical magazine on the side. It was rife with levers, gears, and numerous moving parts. However, hidden among all of that gadgetry was a golden feature: the bored-through cylinder, which allowed metallic cartridges to be inserted from the rear.

White may not have realized the significance of this feature, but another man did. On October 31, 1856, D.B. Wesson wrote:

I notice in a patent granted to you under date of Apr. 3, 1855, one claim =viz= extending the chambers of the rotating cylinder right through the rear end of said cylinder so as to enable the said chambers to be charged from the rear end, either by hand or by means of a sliding charger operating substantially as described. Which I should like to make arrangements with you to use in the manufacture of firearms. My object in this letter is to enquire if such an arrangement could be made and if so, on what terms. By replying to the above at your earliest convenience you note conforming at favor.

I am sir, yours respectfully,

D.B. Wesson

Those simple words set off a chain of events that would ensure Smith & Wesson’s success while frustrating the competition until 1872—bypassing the Civil War and well into westward expansion.

Smith & Wesson’s Monopoly on the Market

The concept was simple and elegant. Rimfire cartridges, pioneered by Smith & Wesson, were the perfect match. Initially available only in .22 caliber, they soon expanded to .32 caliber, and by the end of the Civil War, rimfire cartridges up to .56 caliber were widely available.

A royalty agreement was struck between S&W and Rollin White. While White should have become wealthy from payments made per gun, a sneaky clause in the agreement required him to defend any legal challenges to the patent. Numerous infringements resulted in disastrous legal expenses. Even though the courts ruled in his favor, White never recovered financially—but, as always, the lawyers came out on top.

How Competitors Responded

So, there you were—an arms manufacturer, salivating at the possibilities and watching S&W soak up all the profits. What did you do?

Different manufacturers took different approaches:

-

Some played by the rules, developing firearms that circumvented the Rollin White patent.

-

Others ignored the patent entirely and produced revolvers that infringed upon it.

The Innovators: Those Who Played by the Rules

These companies sought alternative solutions to remain compliant:

-

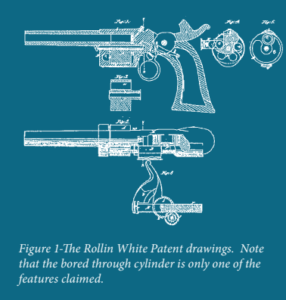

Plant Manufacturing Company (New Haven, CT) & Eagle Manufacturing Company (New York, NY)

-

Developed front-loading pistols using proprietary metallic cartridges.

-

Their “cup fire” cartridges had a cupped base containing fulminate and could be loaded from the front.

-

-

Connecticut Arms Company (Norfolk, CT)

-

Manufactured a graceful pocket pistol using the same cup fire cartridges as Plant and Eagle.

-

-

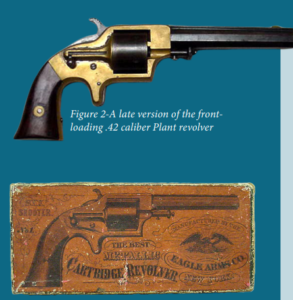

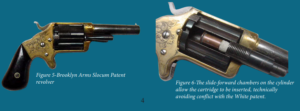

Brooklyn Arms Company (Brooklyn, NY)

-

Created a complex pistol where sliding chambers moved forward to load standard .32 caliber rimfire cartridges, barely avoiding patent restrictions.

-

Also produced an infringing version.

-

-

Moore’s Patent Firearms Company (Brooklyn, NY) & National Arms Company (Brooklyn, NY)

-

Developed a compact spur trigger revolver utilizing the .32 caliber “teat fire” cartridge.

-

The teat fire cartridge had a flared mouth and a protruding “teat” filled with fulminate, allowing it to be loaded from the front.

-

National Arms also produced a .45 caliber version.

-

The .32 caliber version was highly successful, with 30,000 units produced.

-

-

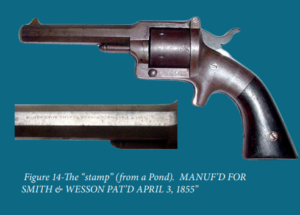

Lucius Pond

-

Designed a complex revolver where chamber liners slid forward to accept .32 caliber rimfire cartridges before returning to position.

-

Also produced an infringing version.

-

-

Colt Patent Firearms Company

-

Avoided direct infringement by introducing the Thuer Conversion, a kit allowing percussion revolvers to be converted into cartridge revolvers.

-

Though complex, it had a few advantages:

-

It was removable, allowing guns to revert to percussion use.

-

It was a full-size military pistol.

-

The cartridges were reloadable.

-

-

However, it failed to gain popularity, and much of the inventory was sold to foreign buyers.

-

The Infringers: Those Who Ignored the Patent

These companies blatantly disregarded White’s patent and faced lawsuits:

-

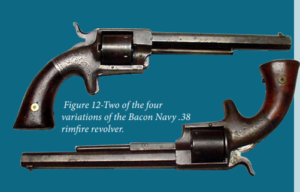

Bacon Manufacturing Company (Norwich, CT)

-

Produced numerous infringing pistols, primarily in .38 rimfire.

-

Four distinct variations are known.

-

-

Brooklyn Arms Company (Brooklyn, NY)

-

Manufactured a .32 caliber rimfire version of the Slocum patent revolver.

-

-

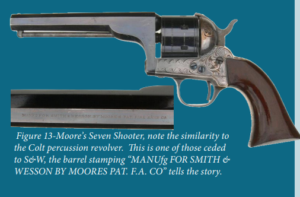

Moore’s Patent Firearms Company (Brooklyn, NY)

-

Produced the popular Moore seven-shot revolver, which clearly infringed on S&W’s patent.

-

Shamelessly copied many mechanical details from Colt’s percussion revolvers.

-

-

E.A. Prescott (Worcester, MA)

-

Manufactured a series of revolvers, one of which closely resembled the Smith & Wesson No. 2 Army—a double insult!

-

-

Lucius Pond (Worcester, MA)

-

Produced both compliant and infringing pistols, as seen in the earlier section.

-

Legal Battles and Their Consequences

When lawsuits were settled, the courts ruled in favor of Smith & Wesson. As part of the settlement, remaining inventory from infringing manufacturers was seized and marked in various ways.

Many companies tried to “jump the gun” as the 1872 expiration date of the Rollin White patent approached. This explains why Colt’s first true cartridge revolver, the 1872 “Open Top”, was released only after the patent expired.

Conclusion & Further Reading

The Rollin White patent profoundly shaped the evolution of American firearms. Many companies tried to find loopholes or defy the restrictions, leading to ingenious workarounds and costly legal battles.

In a future article, we’ll explore Colt’s experimental toolroom and how they converted leftover percussion revolvers into cartridge firearms.

For more details, check out these references:

-

Jinks, Roy – History of Smith & Wesson, Beinfeld Publishing, 1977.

-

McDowell, Bruce – A Study of Colt Conversions and Other Percussion Revolvers, Krause Publications, 1997.

-

Winant, Lewis – Firearms Curiosa, Greenberg Books, 1955.